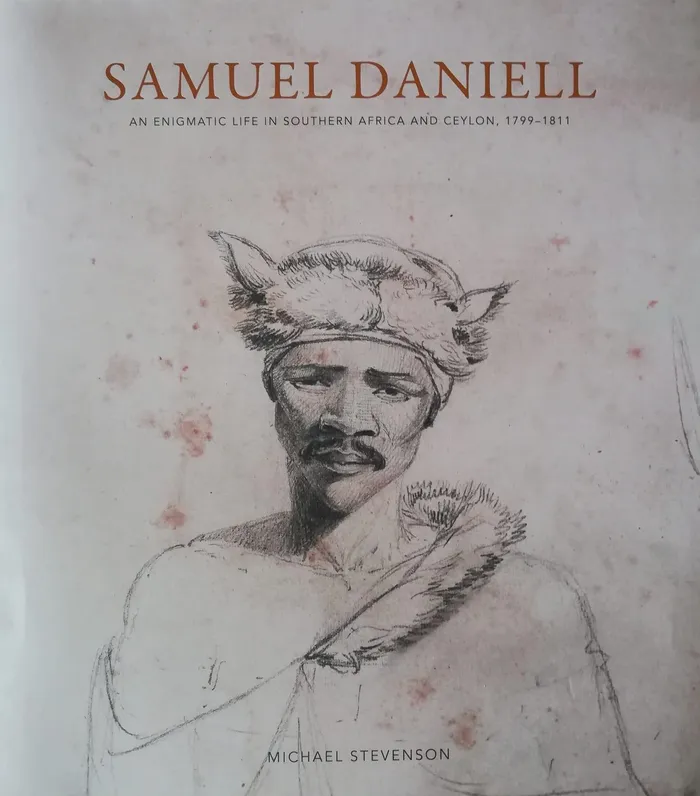

Cover of the landmark biography of Samuel Daniell.

Image: Supplied

AT the beginning of September 1799, a young Englishman of limited means set sail for Cape Town as part of the entourage of the new Governor, Sir George Yonge. Three months later, the ship docked in Table Bay.

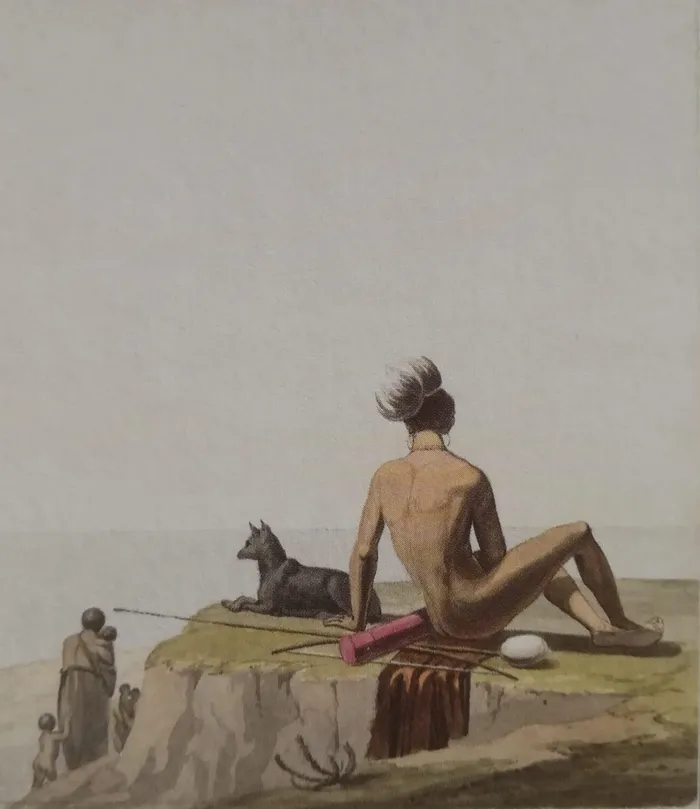

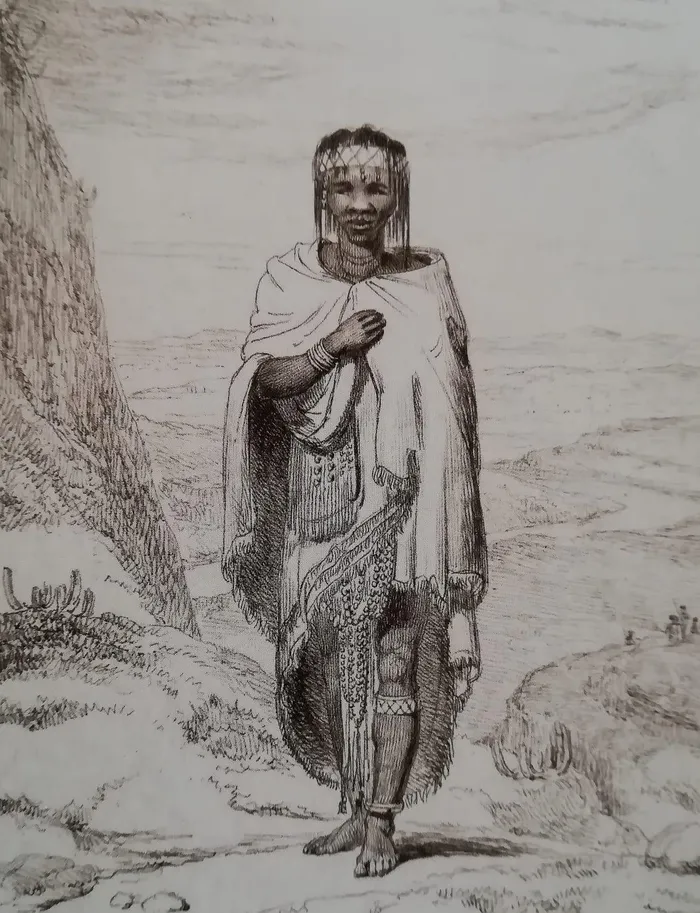

That young Englishman, Samuel Daniell, would spend the next four years in the Cape, sketching the people, animals and landscapes he observed on two journeys into the interior. Some of his pictures were the first accurate European depictions of the Khoisan of the Orange River, the Tlhaping ( southern Tswana) and the Xhosa of the Eastern Cape. His pictures are also a valuable record of their traditional life before it was irrevocably impacted by colonialism.

The arrival of Daniell at the Cape came at a pivotal moment: the Dutch had last control of the colony to the British in 1795, ushering in the First British Occupation of the Cape (1795-1803). Although Daniell was the most accomplished artist of this period, his name and oeuvre slid into oblivion after his death in Ceylon in 1811.

Portrait of Samuel Daniell by his brother William, circa 1799.

Image: Supplied

In Samuel Daniell : An enigmatic life in Southern Africa and Ceylon 1799-1811, published by Jonathan Ball, 2025, Michael Stevenson resurrects the career of Daniell. It has been a 30 year odyssey for the author largely because Daniell left behind so little written evidence, and his art, some of it lost, has been widely scattered.

He has overcome the paucity of information by turning to the accounts of his contemporaries as well as Daniell’s older brother William and uncle Thomas, both of whom were respected artists.

Daniell’s date of birth is usually given as 1775 which Stevenson also gives (p30) but then later, confusingly, states as 1774 (p93). An artist who knew Daniell’s uncle and brother secured a junior position in Sir George Yonge’s entourage, a post which Daniell reluctantly accepted.

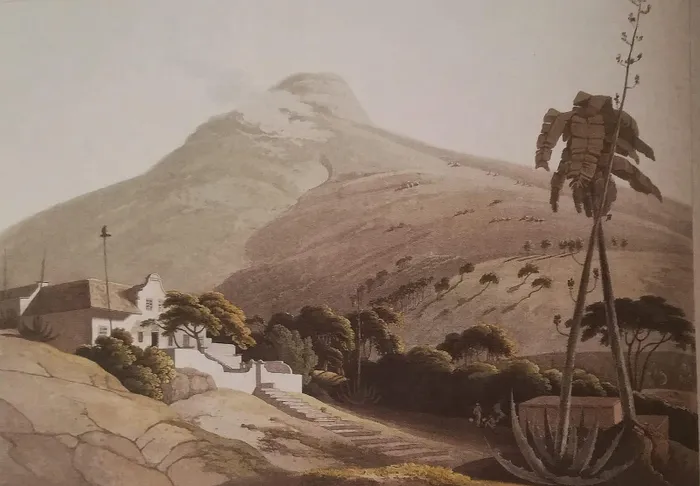

The view of Lion's Head and the Cape Dutch homestead, Bellevue.

Image: Supplied

A patron was a useful entrèe into the tightly- knit Cape society dominated by the aristocratic Lady Anne Barnard. Through Yonge, Daniell was soon appointed as secretary to William Somerville, who was taking up a post in Graaff-Reinet. The two men formed a friendship which was severely tested a year later.

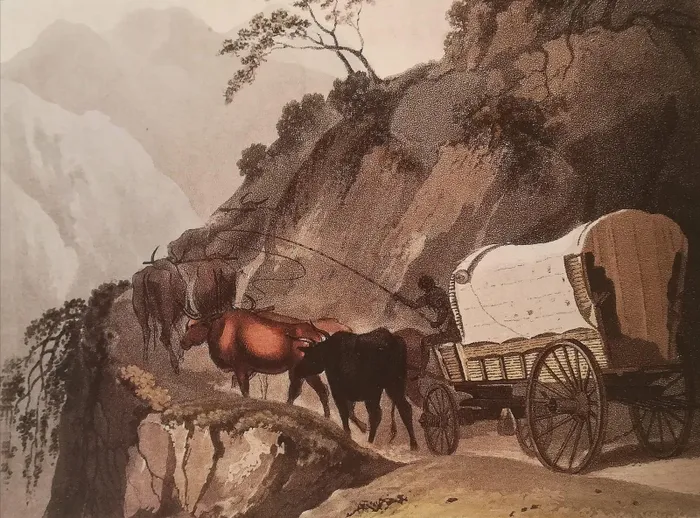

Travelling into the interior in 1800 was fought with difficulty. Finding a passable route or a place to cross a river made it necessary to descend steep precipices strewn with rock or covered in thick clumps of brushwood through which a road had to be cut. A single false step might lose both wagons and oxen. If a descent was treacherous, the ascent was only possible if double teams of oxen were yoked together.

Passing a kloof captures the perilous difficulty of travel in 1800.

Image: Supplied

Daniell was struck by the beauty of the immense, open landscape which belied the encroaching Trekboers into the San community and the resultant conflict. His portrayals of the indigenous people were sensitive and perhaps because of the hospitality he experienced from the Boers, so were his scenes of Boer life.

He was not unaware, however, that their good qualities could be obscured by “their cruel and inhuman treatment of the poor Khoisan who are forced into their employ.”

The military station and block house at Algoa Bay.

Image: Supplied

On the homeward journey, the party passed Algoa Bay. Daniell’s images are amongst the earliest of the settlement which grew into the town of Port Elizabeth.

The first journey ended in April 1801, a year after it had begun. His arrival coincided with the departure of Governor Yonge, recalled to England in disgrace. Without his patron, Daniell accepted an invitation to stay with Lady Anne Barnard and her husband Andrew, at the Vineyard. It began well, but ended very badly.

Lady Anne Barnard's copy of Daniell's painting dispenses with the mountain with which Daniell brings depth to his painting.

Image: Supplied

He had not been their guest long when Lady Anne privately entered Daniell’s room and copied many of his drawings. He discovered what she had done and when he reproached her, she confessed her misdeed and “was ashamed and burnt them all, to an enormous amount, for she had been very industrious”. She bound him to secrecy; the next day her husband offered him a position in the secretary’s office at $100 pa.

Halt of a Boer family. The Trekboers were often seen in the frontier country.

Image: Supplied

Daniell then decided to visit Plettenberg Bay, but before he left in July, he deposited all his drawings with Somerville, explaining, universally as it turned out, why he was doing so. Somerville was something of a gossip and in that tiny Cape clique, the story of Lady Anne’s deed was soon on all their lips.

Somerville was rightly blamed, but Daniell had made an enemy of the influential first lady of the Cape. From the surviving drawings by Daniell and Lady Anne, the extent of her copying is clear.

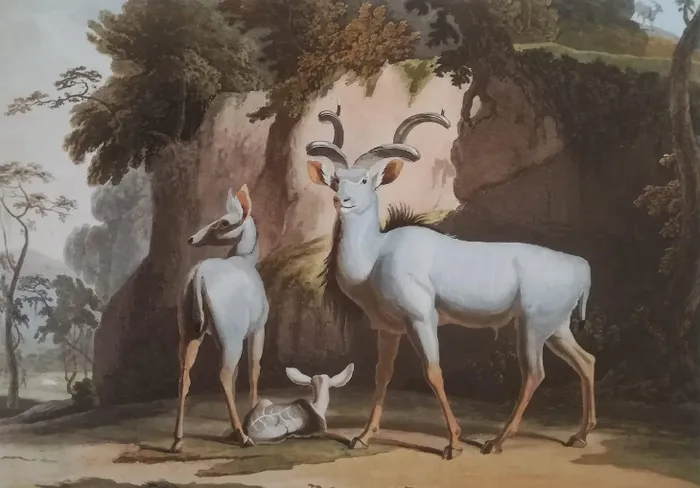

Daniell noted the proliferation of kudo in the wooded country.

Image: Supplied

His residence in her home gave her opportunity but on another level, she no doubt recognised the quality and importance of his drawings. If she considered the consequences, she probably believed that her high birth and social standing would protect her. But for Somerville, it very nearly did.

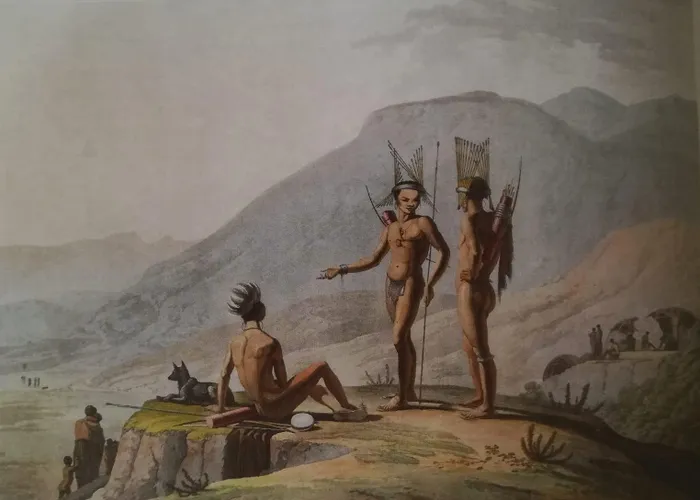

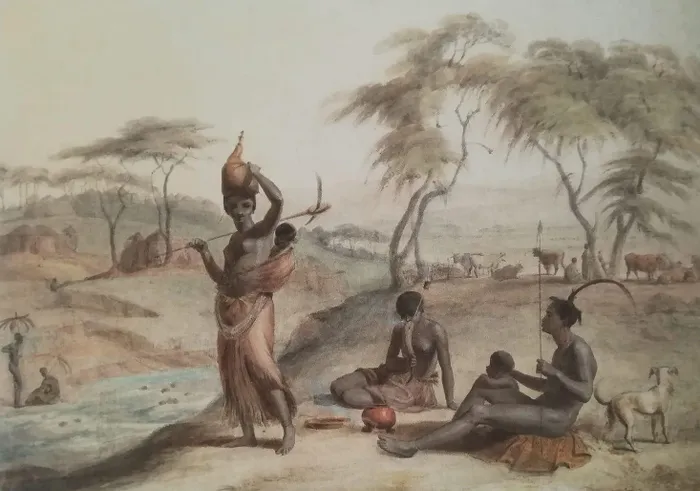

Khoisan armed for an expedition by Samuel Daniell.

Image: Supplied

By now it was propitious if Daniell was no longer in Cape Town and so a few weeks later, at the prompting of Andrew Barnard, Daniell was included in the expedition to barter for cattle beyond the Orange River. After three years of poor harvests and a shortage of cattle, famine was a possibility in the Cape. Led by Chief Commissioners Truter and Somerville, the expedition was not a success.

A Khoisan village on the left bank of the Orange River.

Image: Supplied

Cattle were not plentiful and the goods offered for barter less than impressive. Somerville, interestingly, respected the Tlhaping people’s reluctance to trade: “They have enough sense to value their oxen more than beads, knives or other baubles offered in exchange for them.

The expedition encountered animals still unknown to science such as impala and the blue wildebeest. The quagga were still plentiful and among “the most common and abundant of the large animals on the barren plains.” It was still possible to see herds of up to 50 000 springbok migrating from one tract of country to another.

Sketch of a Khoisan woman. Daniell's drawings were particularly sensitive.

Image: Supplied

Shortly after the expedition arrived back in Cape Town in May 1802, news of the treaty of Amiens reached them. The first British Occupation was over. All former Dutch possessions (except Ceylon and Trinidad) were to be transferred back to the Batavian Republic. The Cape was handed over in February 1803, and Daniell returned to England.

There he worked on producing his ambitious African Scenery and Animals.

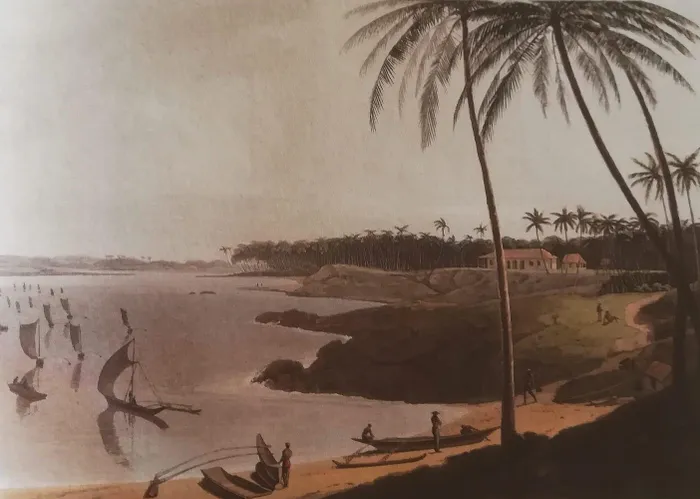

Fishing cove near Colombo, Ceylon. Daniell died in Ceylon in 1811 aged 36.

Image: Supplied

The first 15 plates were published in 1804, but before the second set of 15 was issued, Daniell set sail for Ceylon (today Sri Lanka) which was still a British possession. He remained there, sketching and painting until his untimely death in 1811, aged 36. He fell victim to a fever which the “ cure - a combination of bloodletting, doses of opium and laxatives - probably worsened. He was buried in an unmarked grave in Colombo.

Daniell sketched this scene on his second journey into the interior.

Image: Supplied

In later years, Daniell’s brother William self- published some of Daniell’s work, but in 1831 and 1836, he auctioned most of it (as well as his own) for financial reasons. As the author comments, how different the reputation of the two brothers would have been if their work had been preserved intact in a museum collection rather than scattered so widely.

Michael Stevenson has brought together most of Daniell’s surviving oeuvre, an outstanding achievement. Extraordinary to note, there were a few private collectors who refused permission for their examples of Daniell’s work to be published.

Not only has the author cast an expert eye on Daniell’s art, placing it in the context of its era, but he has also opened a window onto his life. Only if a trove of letters or diaries one day come to light, will it be possible to fully open that window.

What fascinated Daniell and those who saw his prints when first published in the early 19th century, are equally fascinating to the reader in the 21st century. For the 19th century reader, it was something new, for those in the 21st, it is for something largely vanished.

A quagga. These animals had not yet been hunted into extinction.

Image: Supplied

With its full colour reproductions, catalogue raisonne and detailed text, this publication had re-introduced the forgotten figure of Samuel Daniell into the rich tapestry of South Africa’s history.