José Manuel de Prada - Samper interweaves his personal experiences in the Northern Cape and Karoo in his new book, Fading Footprints: In search of South Africa's first people.

Image: Supplied

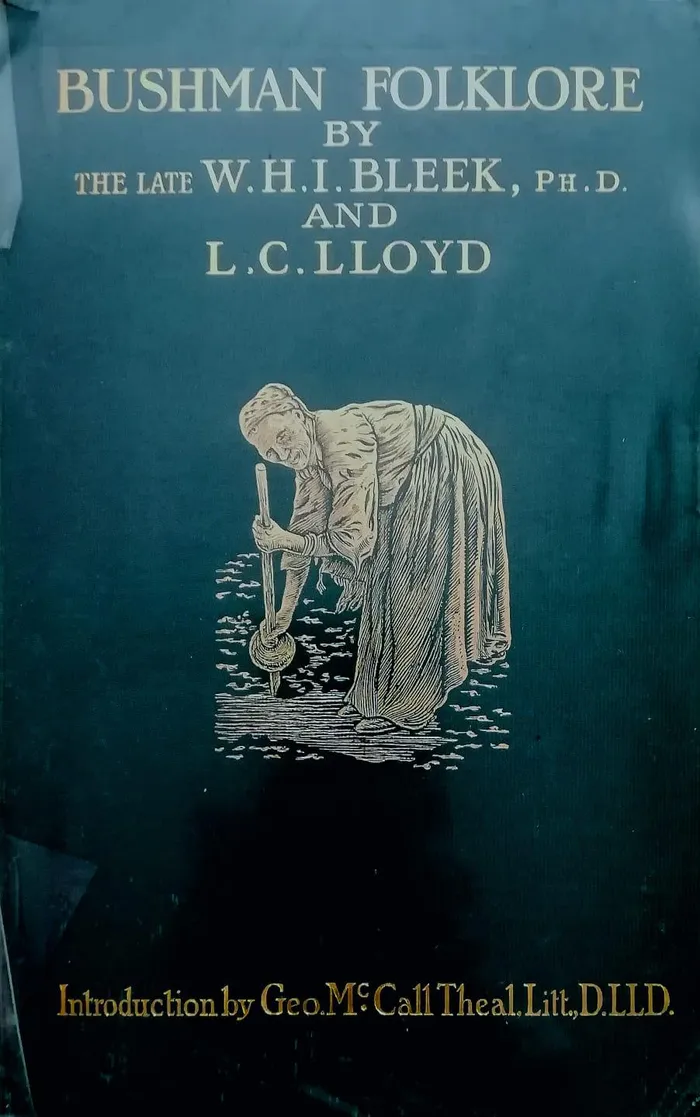

IN 1986, a 23 year old Spanish student spent part of his summer months attending courses at Cambridge in England. One day he noticed a second hand shop called "The Haunted Bookshop”. There he spotted an intriguing old volume bound in green covers with a picture of an old hunched woman embossed in gold. Entitled Specimens of Bushmen Folklore by Bleck and Lloyd, its price of $30 was beyond the means of a student.

The cover of the 1911 first edition of Bushmen Folklore with the old hunched woman embossed in gold

Image: Supplied

Published in 1911, he also reasoned that there must be more recent publications on the natives. But the book stayed in his mind. The unexpected receipt of $25 settled the matter. He quickly returned to the shop and bought the book. On that summer day he had no way of knowing that it would awaken a lifetime’s quest to research and understand the oral tradition of the lxam folklore.

In his new book, Fading Footprints: In search of South Africa’s first people (Jonathan Ball, 2025), Jose Manuel de Prada-Samper interweaves his personal experiences in the Northern Cape and Karoo beginning in 2005 and 2006, with the historical records of Bleek and Lloyd as well as the impact of Cape colonial officials and farmers on the lxam.

What the author would not have known in1986, is that Bleek and Lloyd’s book might have been published as far back as 1911, but together with their archive, remains the foundation on which all subsequent research has been built. As other writers have done in recent years, he delves into its background.

Wilhelm Bleek (1827-1875) was born and educated in Germany, where he studied African languages. He came to Natal in the 1850s with Bishop Colenso and learnt the Zulu language before settling in Cape Town under the patronage of Sir George Grey, whose library he catalogued

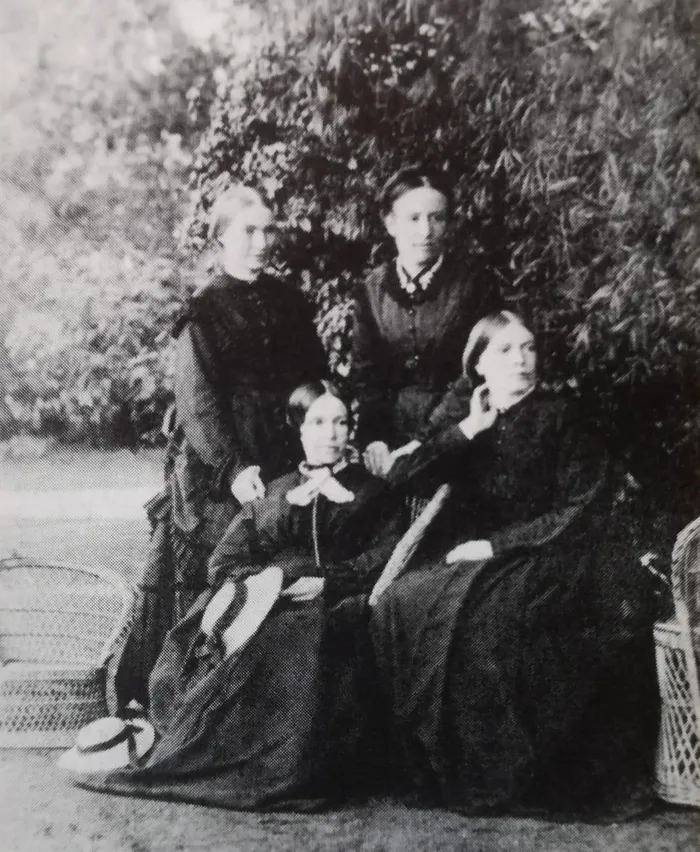

In 1861, he met Jemima Lloyd, one of four daughters of Reverend William Lloyd and his first wife, who died when the girls were still young. The following year Bleek and Jemima married. One of their daughters, Dorothea, would continue the work of her father and aunt Lucy Lloyd.

The old St Paul's church in Durban as the Lloyds would have known it before it was destroyed by fire in 1906. Reverend Lloyd was the first incumbent.

Image: Supplied

Rev Lloyd was the rector of St Paul’s church and later Archdeacon of Durban. Despite being a man of the cloth, he lacked many of the Christian virtues one would have expected of a man in his position. After the death of his first wife, he married Ellen Norman with whom he had 13 more children, which resulted in mental health problems for the poor women. His first wife had bequeathed £3000 to each of her four daughters, providing an annual income of £100, enough to live modest, independent lives.

Shortchanged of Christian values, Rev Lloyd was also short of cash. He not only considered it the duty of his daughters to support their stepsiblings, but tried to get his hands on their inheritance. Three resisted and were eventually expelled from the house; the eldest sister Fanny, hoping their father would be kinder to them, parted with some if not most of their inheritance, to no avail: she too was cast out.

After Jemima Lloyd and Bleek married, they settled in Mowbray, Cape Town. In time, her three sisters came to live with the couple. Two were able to support themselves and Fanny, who needed their assistance due to the machinations of their father. Blessed with a kindness the reverend lacked, they also managed to assist their stepsiblings from time to time.

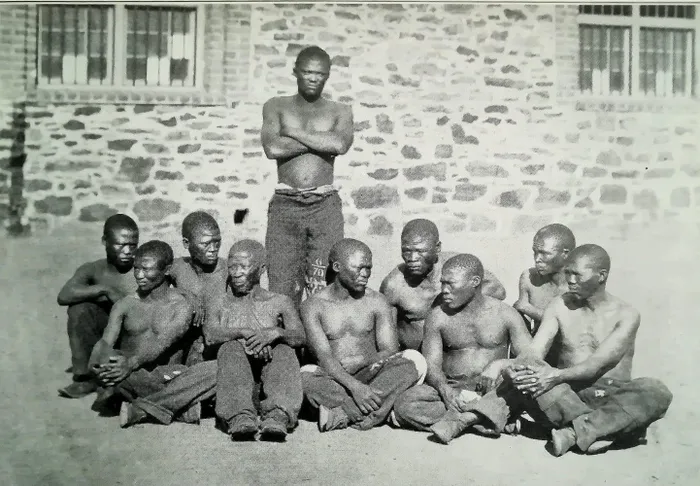

lxam prisoners at the Breakwater convict station, circa 1871.

Image: Supplied

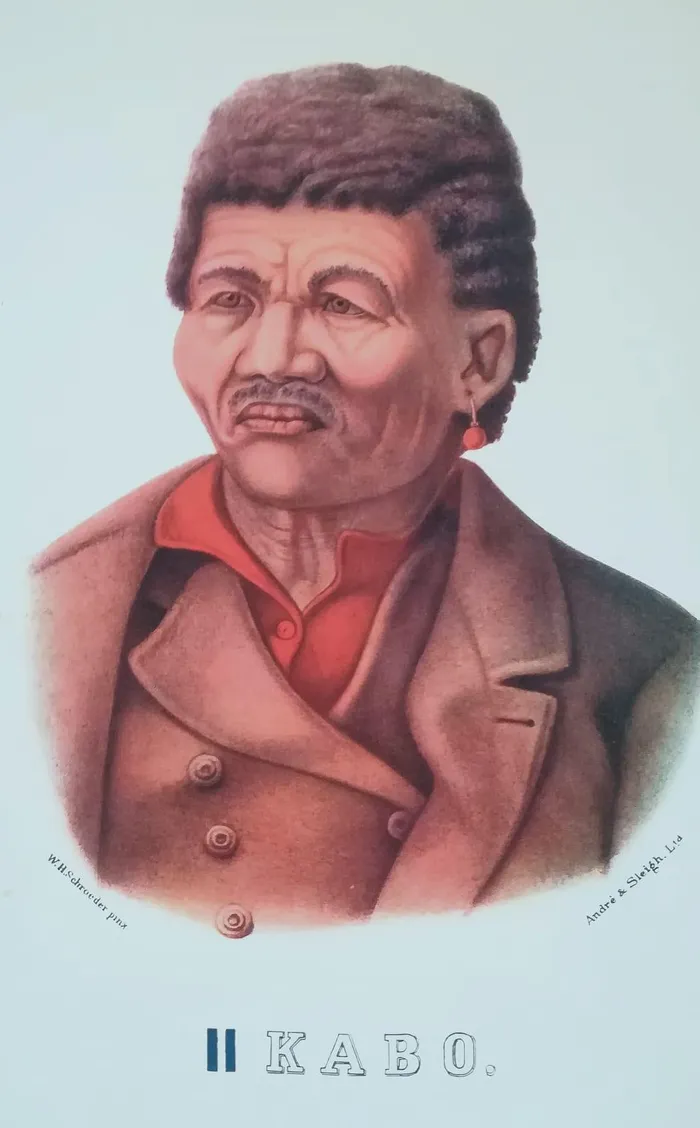

In this somewhat unusual household, Lucy Lloyd found her calling. She developed a keen interest in her brother-in-law’s research into the lxam language and folklore, establishing a fraternal and intellectual partnership with Bleek. In 1870, an opportunity arose when two lxam prisoners were released from the Breakwater convict station into the custody of Bleek. Neither prisoner was kept under lock and key and, in effect, became members of the household. The older prisoner, ll Kabbo, became the man they called their first teacher. It was from him in particular, that they learnt the Ixam language, both becoming proficient.

Lucy was involved from the outset, in fact she spent more time with them as Bleek was at Grey’s library during the day. But Bleek was not well and in 1875 he died aged 48. His youngest daughter (of five) was born posthumously. It was his dying wish that Lucy continue his work. With the sisters in complete agreement, she worked alone with other San teachers, eventually recording 13 000 pages of interviews by 1884.

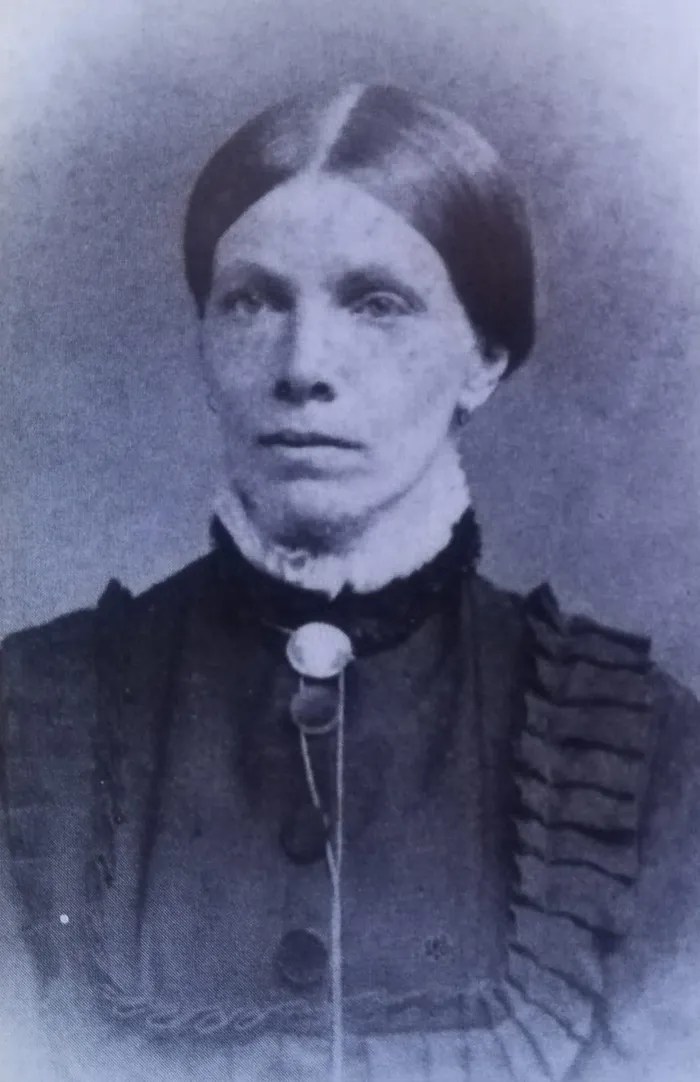

Lucy Lloyd (seated right) with her sisters Fanny, Julia and Jemima in 1873.

Image: Supplied

With Grey’s library without a custodian, Lucy was appointed until a permanent replacement could be found, but at half Bleek’s salary. This lasted until 1880 when she was dismissed. An attempt to have this decision reversed by the Supreme Court was unsuccessful. In the following years, she began to edit and prepare a manuscript for publication. It took years, punctuated by illness, the death of two of her sisters in 1909 and the necessity of creating a typeset to suitably represent the IXam language in print.

It was Lucy who chose the picture of the old lxam woman with the digging stick for the cover. Finally, 36 years after Bleek’s death, Bushmen Folklore was published in 1911. The price of the book was prohibitively expensive - the equivalent of £100 today - but it was well-received. The Cape Times commented on its “extremely interesting illustrations” and the difficulty of printing such a book.

Lucy Lloyd in the 1870s

Image: Supplied

In 1912, the University of Cape of Good Hope conferred the honorary degree of Doctor of Literature on Lucy Lloyd, the first woman to receive such a degree. Part of the citation stated that her work would remain an authority on the language of the lxam, as indeed it has.

She died in 1914 of peritonitis, two months before her 80th birthday. All her books and manuscripts as well as funds were bequeathed to her niece, Dorothea Bleek, who was another of those pioneering woman scholars, whose own work honoured the legacy of her father and aunt.

The portrait of ll Kabbo in the 1911 first edition.

Image: Supplied

In 2010, de Prada-Samper translated some of the Lloyd letters into Spanish for a friend who was a filmmaker. She was surprised that the collaboration of Bleek and Lloyd with their Ixam teachers had never been transformed into a film, despite its cinematic qualities. The potential for a film remains, touching as it could on many aspects of colonial life and policies as well as the human story. As ll Kabbo once told Lucy: “I listen, watching for a story, which I want to hear, while I sit waiting for it.”

The value of Bushmen Folklore was that it managed to preserve the Ixam language before it was lost forever. Even Dorothea believed it was a record of a dying race. de Prada-Samper believed differently. Surely there were lxam descendants who continued the oral tradition of passing down their folklore down the generations?

A lxam family photo taken in 1884.

Image: Supplied

In the final chapter of his book, he records his journey to find those stories which formed the basis of his 2016 book, The man who cursed the wind. The stories have evolved, reflecting the realities of the much-changed existence of the lxam: there is the prisoner who can open a cell door by blowing on the lock and escaping, or who draws a car on the walls and flees in the car.

But he cannot flee back to his original life. “The systematic destruction of a race of men” who were driven to stock theft because farmers had deprived them of their means of subsistence left the lxam vulnerable on the margins of society. There they have remained.

The author is at his most eloquent when writing on the historical plight of the lxam and how an old book opened their world to him. If the pace slows when he recounts his own modern-day travels searching for the remnants of their culture, it does not detract from the overall impact of his book.

One of the later teachers of Bleek and Lloyd, Dia ! Kwain, told of the “time when our heart falls down, that is the time when the star also falls down, for the stars know the time at which we die...” Their star is falling, but echoes of Ixam culture still precariously cling to life.

They are, tragically, fading footprints almost invisible to modern society.

SUNDAY TRIBUNE

Related Topics: