The cover of John Stewart's biography.

Image: Supplied

The Union Buildings in Pretoria are as much a symbol of South Africa as the White House is to Americans or Buckingham Palace is to the British. The architect was Herbert Baker, who uniquely designed not only the key administrative building for South Africa’s new capital, but also (in conjunction with Edwin Lutyens) the key buildings for India’s new capital, New Delhi.

Considering the scope and scale of his work, it is surprising that Baker’s life has never been the subject of a full biography. This omission has been rectified by John Stewart, himself an architect, who has written a fine biography on Sir Herbert Baker, the Empire’s architect. And what a fascinating life he has revealed.

He was fortunate in the support he received from the Baker Family, particularly Sir Herbert’s eldest grandson, Michael, who has preserved an extensive archive of letters and photographs and was on hand to help decipher his grandfather’s handwriting.

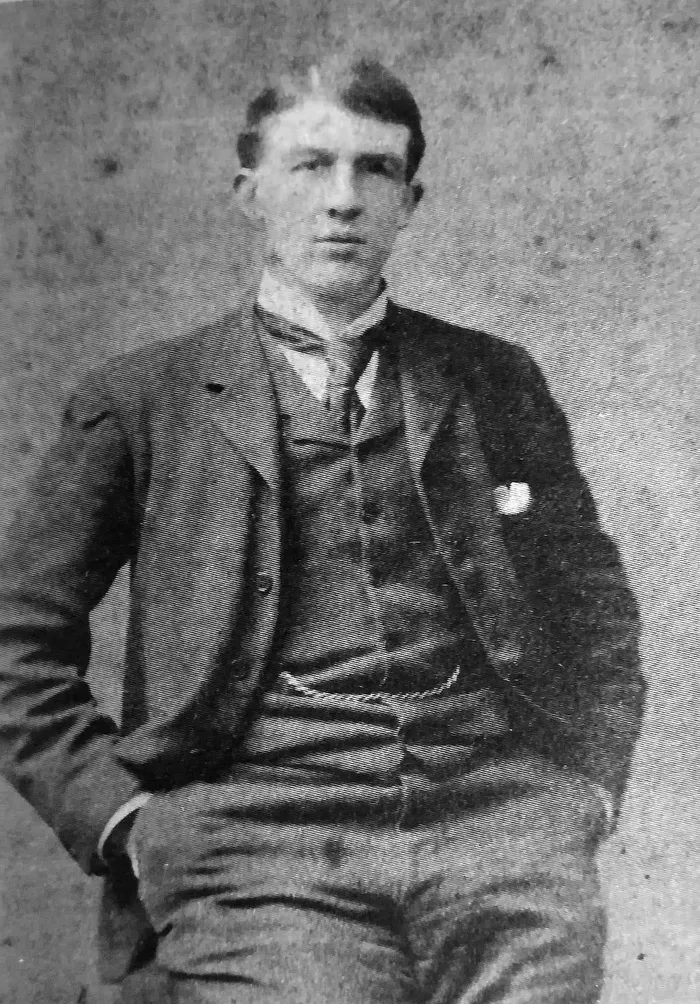

Herbert Baker in 1890 aged 28. (courtesy Michael Baker).

Image: Supplied

Born in Kent in 1862, Baker was a quiet, introverted boy with a strong Christian faith. At school, where he captained both the cricket and football teams, he had resolved to be an architect. An older cousin had an architectural practice in London and it was with him that Baker did his initial training before joining one of the most illustrious firms to complete his education.

Baker (seated centre) as Captain of the school cricket team. A quietly confident leader.

Image: Courtesy of Michael Baker

It was there that he first worked with the young Edwin Lutyens, initially establishing a warm friendship that over 60 years turned to rivalry, loathing and bitterness. Much of the damage done to Baker's reputation would be at the hands of Lutyens.

Baker’s decision to move to the Cape in 1892 was not in search of work as an architect, but to support his younger brother, Lionel, who had seen an opportunity in fruit farming. As new arrivals, the Bakers were introduced to society and it was at a dinner that Herbert found himself seated opposite Cecil John Rhodes, a self-made, energetic man of empire whom Baker much admired.

So starstruck was he that he hardly said a word, prompting Rhodes to enquire about “that silent young man.”

The Great Hall of Government House as Baker originally intended it.

Image: Africana Library

Baker had already started to receive architectural work, but it was the commission from Rhodes for the design of Groote Schuur in 1893 and its rebuilding in 1896 after it was gutted by fire, which was the catalyst for the rapid growth of his practice into the leading firm of architects in South Africa.

Groote Schuur was the first of Baker’s designs to gain recognition beyond South Africa. After Rhodes’s death in 1902, the house was left to the nation as the residence of the Prime Ministers of a United South Africa.

Baker could have remained in the Cape, but the decision of Lord Alfred Milner, the High Commissioner for South Africa, to move his headquarters from Cape Town to Johannesburg in 1901 where he could better manage the reconstruction of the Transvaal after the Anglo-Boer War, presented new opportunities for Baker.

The arrival of General Smuts in January 1917 at the Union Buildings where he addressed the crowd. He had returned from the East Africa campaign in the midst of the First World War.

Image: Pictorial

Milner persuaded him to go to Johannesburg with the prospect of abundant work. This was indeed the case apart from a brief recession when Baker wrote to his future wife, Florence, “Very slack in Johannesburg all millionaires hard up.”

His commissions included mansions for randlords and homes for those who were part of Milner’s inner circle (the kindergarten) as well as for public buildings including Government House and the Pretoria station. And then there were the designs for many churches, which were a reflection of his abiding faith. How Baker and his partners managed the huge workload in Cape Town and Johannesburg was astonishing, particularly as Baker made regular 2000 mile round trips by train.

When C R Ashbee saw Baker's own home, Stonehouse in 1903, he thought it one of the most exquisite pieces of architecture he had ever seen, "springing like a jewel castle from out the rock." This photo was taken soon after its completion.

Image: Supplied

One of Baker’s greatest gifts as an architect was his ability to fuse a site with a building and to exploit its dramatic possibilities. This was apparent in his own home, Stonehouse, built from stone on the Parktown ridge as if it had arisen from the kopje. This skill was to reach its crescendo with the Union Buildings in Pretoria.

He was given a free hand in the choice of site, eventually choosing the dramatic and symbolic Meintjes Kop which dominated the town “as did the Acropolis, the city of Athens”. General Smuts gave Baker the go ahead, understanding that architecture also had its political use, being the ornament of a country.

Baker's own perspective of "Marienhof" designed for Drummond Chaplin. It was later sold to the Oppenheimer family who still own it and who renamed it "Brenthurst".

Image: Supplied

Baker also designed the furniture which was made locally as was the brass and iron work. The gardens, completed in 1919, are also his designs. He was insistent that the kopje be reserved for indigenous trees and shrubs. The building is a tour de force: not only was it completed on time and under budget in only four years, but it sits so naturally on its site that it looks simply obvious. His hope that ministers could look from their windows at “the splendours of the highveld and gather inspiration and visions of greatness,” has too often been in vain.

Baker designed not only grand houses but also small homes, such as the vicarage at St George's church in Parktown, January 2025

Image: Mark Levin

In 1910, Lutyens, who had built a career designing sumptuous country houses, came to visit Baker and was somewhat taken aback at Baker’s achievements. The easy relationship between the friends experienced its first ruffles. Lutyens regarded himself as a wit, but not all agreed: It could be unceasing, tasteless or even childish. On one occasion, he embarrassed Mr and Mrs Pim at dinner when he asked” if there were any pimples?”

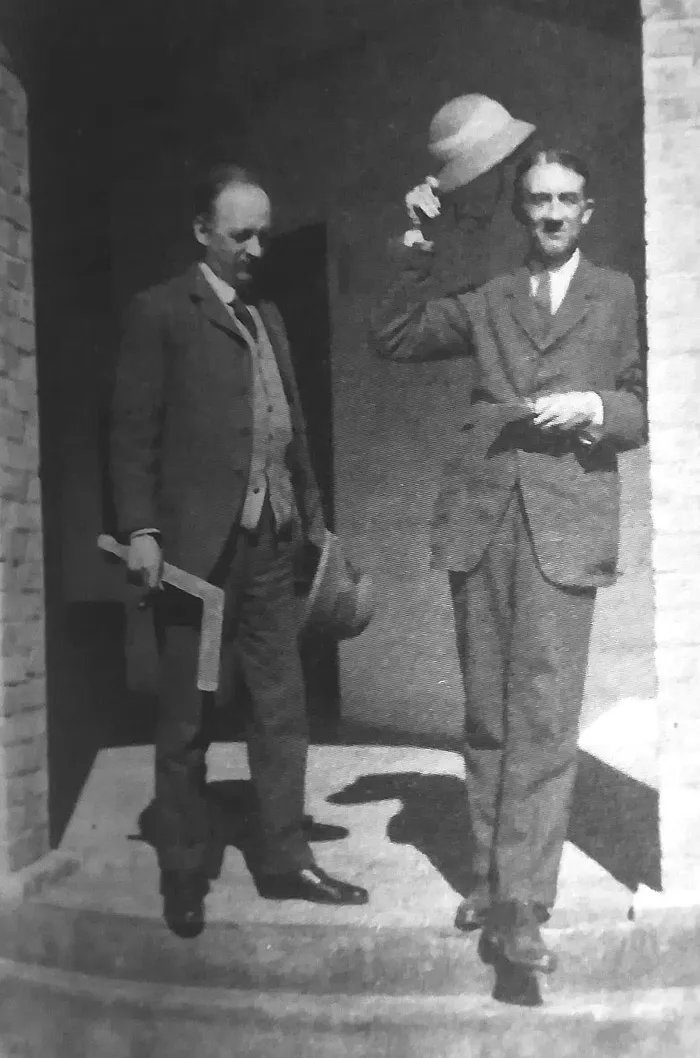

While work was proceeding in Pretoria, Baker and Lutyens were appointed to design the government buildings and Viceroy’s House for New Delhi. The two men concluded an agreement but Lutyens broke the gentlemen’s code and went back on his word, angering Baker. Worse was to come.

Edwin Lutyens, left, with Herbert Baker outside their office in India.

Image: Courtesy of Michael Baker

The Viceroy’s House (designed by Lutyens) would be approached by a Processional (or Kings) Way with the Secretariats (designed by Baker) on either side, acting almost as a pair of sentinels. To achieve this effect and give the Secretariats equal prominence to the Viceroy’s House, a ramp was built which would temporarily obscure the House during the ascent onto the hill before it dramatically reappeared.

Baker’s precedent was the classical architecture of Greece and Rome. Lutyens signed off on the plans, but only after construction had begun did he realise that “his” Viceroy’s House would not be visible during the entire progress along the King's way. He had made a mistake but blamed Baker and demanded the plans be changed.

Accustomed to getting his own way, Lutyens began a succession of appeals, losing each time to the point where one Viceroy called him a spoilt child. Even a meeting with King George V and Queen Mary did not help his cause. With each setback, Lutyens attacked Baker’s reputation with increasing spite and venom.

With every avenue closed, Lutyens embarked on a five-year sulk from which even his own children were not spared: they were forbidden to speak to Baker’s children. In a footnote, the author recounts being driven along the Processional Way with a local Indian guide advising him to “watch the dome” of the Viceroy’s House as it disappeared and reappeared, at which point exclaimed, “see, this is the brilliance of Lutyens!” The irony.

The bust of Herbert Baker in the garden at St George's church, Parktown which he designed as well as its vicarage.

Image: Mark Levin

The final part of Baker’s career brought him back to London. He designed not only South Africa House in Trafalgar Square but also, at the request of Sir Atul Chatterjee, India House. He was responsible for Church House, the Bank of England and even a bridge over the Thames as well as important state buildings in Kenya. And then there were the war memorials honouring the dead of the First World War.

The third floor vestibule of the Bank of England. The photo is from the Bank's archive.

Image: Supplied

He designed 24 memorials for schools and towns, and plagues for churches. At the sites of some of war’s terrible battles, he was responsible for the construction of 112 cemeteries and seven memorials to the missing, including our own Delville Wood memorial in France. It would be remiss not to mention that the famous weathervane at Lord’s cricket ground of “Old Father Time” was presented to the MCC by Baker.

Baker was knighted in 1926. He was also awarded the Royal Institute of British Architecture’s Gold Medal and after his death in 1946, he was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Despite such honours, Baker’s reputation was unfairly tarnished by years of sustained attacks. This may surprise South Africans who regard Baker as one of the county's greatest architects. The author also believed Baker’s life and career were long overdue for reassessment. His biography has done that, revealing that Baker was indeed an architect extraordinaire.

Sir Herbert Baker by John Stewart (Jonathan Ball, 2025) is available at all good book stores.

Related Topics: