The image of Perla Siedle Gibson which appeared on the cover of her autobiography published in 1964 : white dress, red hat and her megaphone.

Image: Supplied

SINCE the end of the First World War in 1918, the month of November is associated with the poppy and the remembrance services held to pay tribute to those who sacrificed their lives in times of war. On the homefront, ordinary citizens from school children to pensioners and housewives” did their bit” to support the soldiers on the frontlines. Their morale-boosting efforts should also be remembered.

One Durban woman who made a unique contribution during the second world war was Perla Siedle Gibson. From 1940 until the war’s end, she stood on North Pier singing to every troopship sailing in or out of Durban. It rose from a chance request. After South Africa entered the war, the Seamen’s Institute opened a canteen at Congella which was managed by Perla’s mother, Amelia Siedle. Wearing a white dress, Perla helped serve refreshments to departing servicemen.

Waving goodbye to a troopship sailing out of Durban.

Image: Supplied

One day, she went down to wave goodbye to one of the departing troop ships. Suddenly, one of the young men who knew she sang, called out to her begging “Give us a song, Ma!” Perla cupped her hands to her mouth and sang “When Irish eyes are smiling”. The sound of her voice - she was a trained soprano - was deeply moving to the young men, many of whom were homesick and uncertain of what awaited them. One soldier later recalled, “there was this opera star singing with the clanging of trucks and the whirring of cranes for an orchestra".

Perla later described this moment as her rendezvous with destiny. It marked the start of her wartime career by a woman “ who had nothing to offer to the cause for which men and women were dying in their thousands than a God-given voice.”

During the course of the war, she sang to over 1000 troop ships and 350 hospital ships. She estimated that three million men listened to her, a plump middle-aged woman in her 50s - she called herself fat - singing popular songs through a megaphone. Come sun or rain, be it at midnight or first light, Perla was there, a solitary figure in her simple white dress and red hat waving a handkerchief as each ship slipped away. They called her the “Lady in White”.

Perla Siedle Gibson was presented with a burnished copper megaphone on board HMS Nigeria. After the war, she donated it to the Warriors Gate Museum.

Image: Supplied

Captain Brook, who commanded HMS Renown, told Perla how much the Navy appreciated her singing. Aware of her reputation, men on board always hoped she would be there to sing in their ship. She never disappointed. Only once did she not sing. That was when Delwara departed on July 17,1940 with the first big contingent of South African troops bound for East Africa.

On board were her two sons, Roy and Barrie, aged 21 and 20. At that time, she had not yet developed the inner strength which sustained her in years ahead, despite her personal emotions.

With Lord Louis Mountbatten of Burma at the Burma Star celebrations in London, 1963.

Image: P S Gibson

Perla drew inspiration from her family, who were high achievers. Her father, Otto Siedle, was a successful businessman who devoted much of his spare time to the cultural activities in Durban. He had a decent bass voice, singing with the choral society and helping to place the Municipal Orchestra on a secure footing.

He had little interest in politics, unlike his wife Amelia, who was a tireless town councillor, eventually serving as deputy Mayor of Durban in 1926/27. Perla was their only daughter who initially trained as a pianist before switching to singing. Her four brothers had a musical bent, but their forte was sport, particularly cricket and rugby. After the war, her younger brother Jack Siedle achieved renown as a Springbok cricketer in the 1920s and 1930s.

Perla receiving a gift from Mrs Peter Maytom, who acted as Mayoress of Durban when her mother - in - law Margaret Maytom was mayor, 1968.

Image: Maritime Museum

The war brought Perla both happiness and loss. In 1917, she married Jack Gibson, who fought in both the First and Second World Wars. Together they had three children, Roy Barrie and Joy. The devastating loss came in March 1918 when Perla’s brother Major Karl Siedle, MC was killed at the Somme. He had been seriously wounded and was on the operating table at a field hospital when the Germans bombed the hospital, claiming it was a camouflaged munitions dump. He was buried near Amiens on the Somme.

On hearing this tragedy, her mother had a heart attack, followed by a nervous breakdown. For weeks she hovered between life and death. Not long after, Perla’s own life was in danger when she fell victim to Spanish flu. She pulled through after a two-month struggle. During this grim period, her three surviving brothers and husband were all on active service.

The sheer scale of the loss of life in World War 1 created a deep-seated need to erect memorials to the war dead. Karl Siedle’s memory was enshrined in a stone clock tower, erected at Kingsmead Cricket ground, where it still stands. A plaque was also unveiled at the Old Fort Chapel.

Capt Power, MBE escorts Perla Siedle Gibson on HMS Bulwark on the occasion of her 80th birthday in 1968.

Image: Maritime Museum

The “war to end all wars” did not. Twenty years later, the next generation was engulfed in a second world war. Perla’s two sons, Roy and Barrie Gibson separated by just a year in age, were inseparable.

Both played in the same rugby team at Glenwood High, swam for the school and followed the same careers at the Sub Nigel gold mine on the Witwatersrand. When war broke out, they both volunteered with 1st Transvaal Scottish. Roy later transferred to the 6th Battalion, Black Watch which was one of the British regiments fighting in Italy. There on March 14, 1944, he was mortally wounded. Roy’s commanding officer later wrote to Perla that in spite of his wounds - he died eight hours later - his only concern was about the safety of the rest of the patrol. He was buried at the Minturno British cemetery in Italy.

The painting by Perla Siedle Gibson of her son, Roy in the uniform of the Transvaal Scottish, which hangs at Gibson House, Glenwood High School.

Image: Mark Levin

Perla had a premonition of Roy’s death, an undefined depression that was a prelude to that moment some two weeks later when her fear was confirmed. Ten days later, her mother died. Despite her personal loss, when she received word that a troop ship crowded with South Africans was sailing for Italy, she went down to the docks and took up her familiar position on North Pier.

Those on board knew that she had received news of her son's death four days earlier and were not expecting Perla to be there. But there she was. There was hardly a man on board who hadn’t a tear in his eye. One officer exclaimed, “God bless her - what guts!”.

Perla Siedle Gibson with a painting she did of her family in uniform: Barrie, Joy, her husband Jack, and Roy.

Image: P S Gibson

After the war, a plaque in memory of Roy was placed at the Old Fort Chapel beneath that of his uncle Karl. Roy’s brother Barrie unveiled it. Glenwood High School named its boarding establishment Gibson House in his honour. Painting was another of Perla’s skills. She presented a portrait she had painted of her son to the school. It still hangs in Gibson House.

During the war, some of the greatest liners afloat called in at Durban, including the Ile de France, the Mauretania, the Nieuw Amsterdam and many of the Castle ships, all converted into troop carriers. Perla sang to them all in that rich voice which "embraced people in a bear - hug and wrung tears from them.”

Perla Siedle Gibson singing all the old favourites at the Royal Albert Hall concert in 1963.

Image: P S Gibson

Although she officially sang for the last time on Christmas Eve 1945, Perla occasionally sang on special occasions such as to the South African airmen embarking for Korea in 1950. One commemorative event which gave her much pleasure was the Burma Star Association concert in 1963 where she sang all the old favourites at London’s Royal Albert Hall, to wild applause.

Not long before her 80th birthday in April 1968, Perla lost her right eye in a gardening accident. From her hospital bed at Parklands, she quipped that her love for the navy was well-known, but to emulate Lord Nelson and lose an eye was altogether too tough.

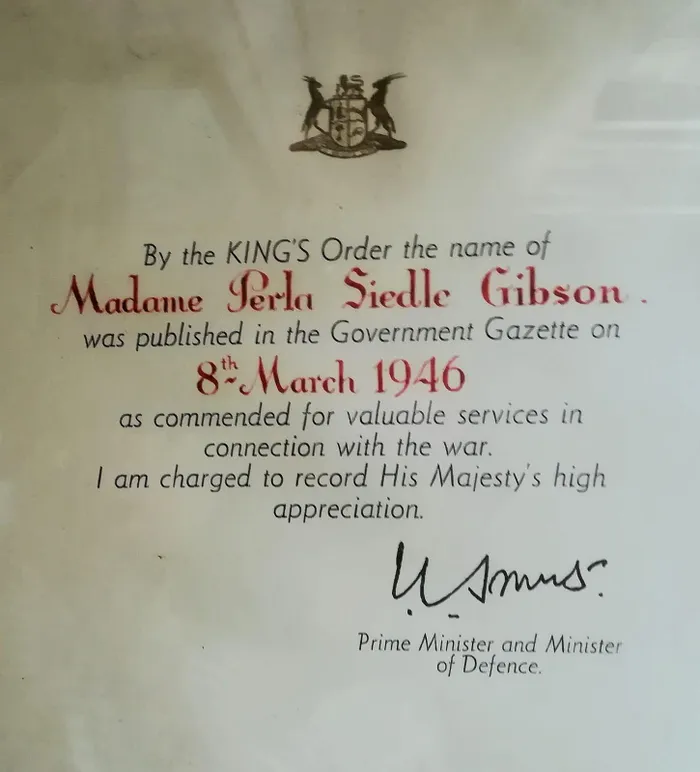

In 1946, Perla Siedle Gibson received a commendation for valuable service during the war from King George VI. The order was signed by the Prime Minister, General Jan Smuts.

Image: Maritime Museum

She was more than ready for her 80th birthday, deservedly enjoying the fuss made of her. She received many tributes in her lifetime, but the one she would probably have most appreciated was the bronze statue created by her niece, Barbara Siedle. Unveiled by Queen Elizabeth ll in 1995, it now stands at the Port Natal Maritime Museum on the Esplanade.

The bronze statue of Perla Siedle Gibson by her niece at Durban's Port Natal Maritime Museum. It was moved there in 2016.

Image: Mark Levin

Perla died on March 6, 1971, a few weeks shy of her 83rd birthday. Her sense of humour, effervescence and ready smile were all part of the warmth she radiated. If her name had gradually faded, now is the time to remember the legacy of the “Lady in White”.

Perla Siedle Gibson at an exhibition of her paintings at the Zululand Show, June 1968. She told a reporter, "I love life. I love people. I shall go on singing."

Image: Maritime Museum

Perla once wrote that her fulfilment as an artist was not in a concert hall, but on a grime-encrusted stretch of a dockside quay in Durban.

Related Topics: