Cover of Martin Plaut's much - needed overview of African slavery.

Image: Supplied

WHENEVER the topic of slavery is raised, it is usually the Trans-Atlantic trade, yet it is only a fragment of a much longer story of human bondage and suffering.

There are also popular misconceptions about it. The largest trader across the Atlantic was not the British, but the Portuguese who accounted for 47% of all slaves transported across the Atlantic, mainly to Brazil, numbering some 5.8 million Africans.

Of course this does not lessen Britain’s guilt, being responsible as it was for the transport of about 3.2 million Africans, mainly to the Americas and the Caribbean.

Slaves and slave dealers in Zanzibar. So lucrative was the trade that Oman's Sultan transferred his capital to Zanzibar.

Image: Supplied

Much less known was the sizeable Indian Ocean trade which was responsible for the transport of over 12.5 million Africans, a figure slightly higher than that of the Atlantic trade. The Trans - Sahara trade at over 9.3 million was not far behind. Then there was Africa’s internal slavery which survives in at least five countries: Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Libya and Sudan.

In Unbroken Chains: a 5000 year history of African enslavement (Hurst, 2025) former BBC Africa Editor, Martin Plaut, provides a much-needed survey of slavery in Africa. He reveals to the general reader the extraordinary length and scope of African slavery and how ingrained it is in many societies.

Africans engaged in the trade centuries before external powers intervened, yet they and Muslim societies resist engaging with the subject. It is as if their overwhelming silence erases their own role and complicity.

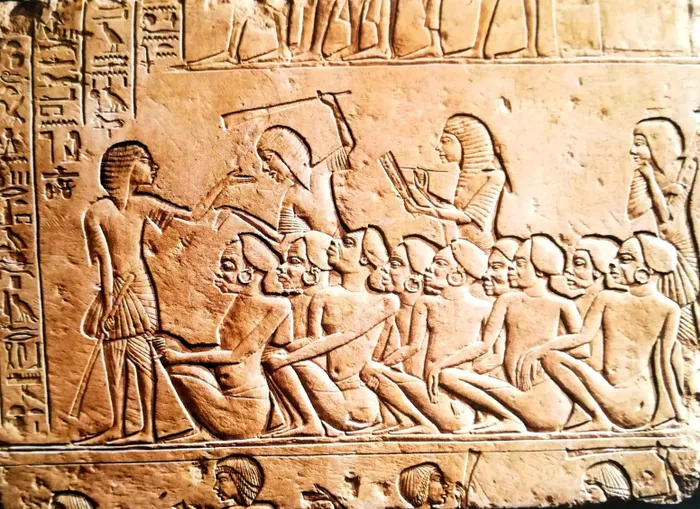

A limestone relief of Nubian prisoners sitting submissively on the ground, guarded by Egyptian soldiers armed with sticks, circa 1330 BC. Bologna Museum

Image: Bologna Museum

Among the earliest authenticated forms of servitude was down the Nile River and across the Sahara. Dating back 5000 years, it has continued almost without interruption.

Slaves performed many functions in Egyptian society from servants and concubines, to soldiers defending the nation from its enemies. However, contrary to popular belief, it was not slaves who built the pyramids but skilled labourers who were both prized and respected.

Over centuries, the practice of slavery was carried over the Mediterranean, the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. Raiding parties into Nubia captured thousands of inhabitants to ensure a steady supply of slaves at trading posts. The cruelty, abuse and disease exacted a terrible toll on the slave caravans during the long march from Sudan to Egypt.

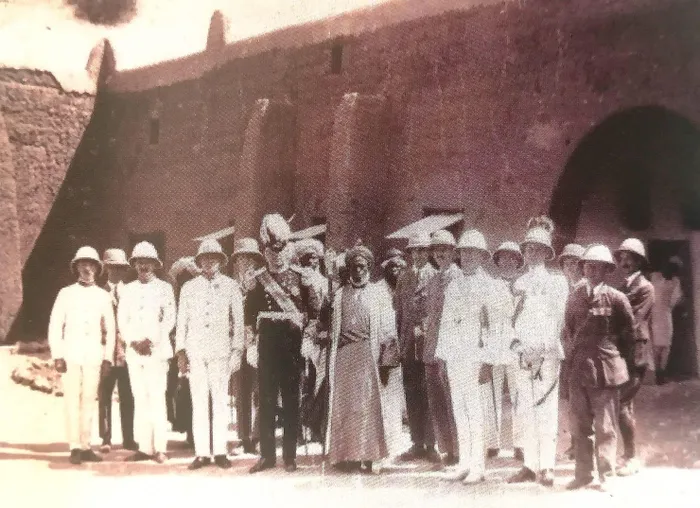

The High Commissioner of Northern Nigeria, Sir Frederick Lugard (in plumed hat), meeting the Emir of Katsina in 1907.

Image: National Archive, Kew

Plaut provides some surprising snippets: during the American Civil War, supplies of cotton from the American south dropped. Consequently, the demand for slaves needed to increase cotton output in Egypt rose by over 5000 each year from 1861 - 1864. Up to 30 000 slaves were sent to work in villages on the Nile Delta.

More slaves were transported on the Indian Ocean route than over the Trans - Atlantic. Of all the Arab nations, Oman probably had the greatest impact. Slavery in southern Arabia was older than the Islamic religion with a flourishing mart for slaves in Muscat. Omanis had traded along the East African coast since the first century, interacting with local Swahili rulers who sent slaves to Arabia from as early as the tenth century.

Ethiopian slaves accompanying their masters to present Emperor Haile Selassie with funds to help defend their country from the Italian invasion, 1935.

Image: Bodleian Library, Oxford

With the development of the clove industry in Zanzibar, the demand for slaves rocketed. By the 1830s, the slave population on the island had risen from 15 000 to more than 100 000, but with the soaring mortality rate, the labour force had to be replenished by between 9000 and 12 000 slaves annually. So great was the Omanis' penetration of the interior in search of slaves that by 1850 they had reached the Angolan coast.

The explorer David Livingstone even met Arabs from Zanzibar in what is today Namibia's Caprivi Strip. Travelling with them over a period of four years, he was horrified by what he witnessed, particularly a massacre in 1871 when Arabs fired on villagers, leaving hundreds dead. His account, published in New York and London helped invigorate the British Anti - Slavery campaign.

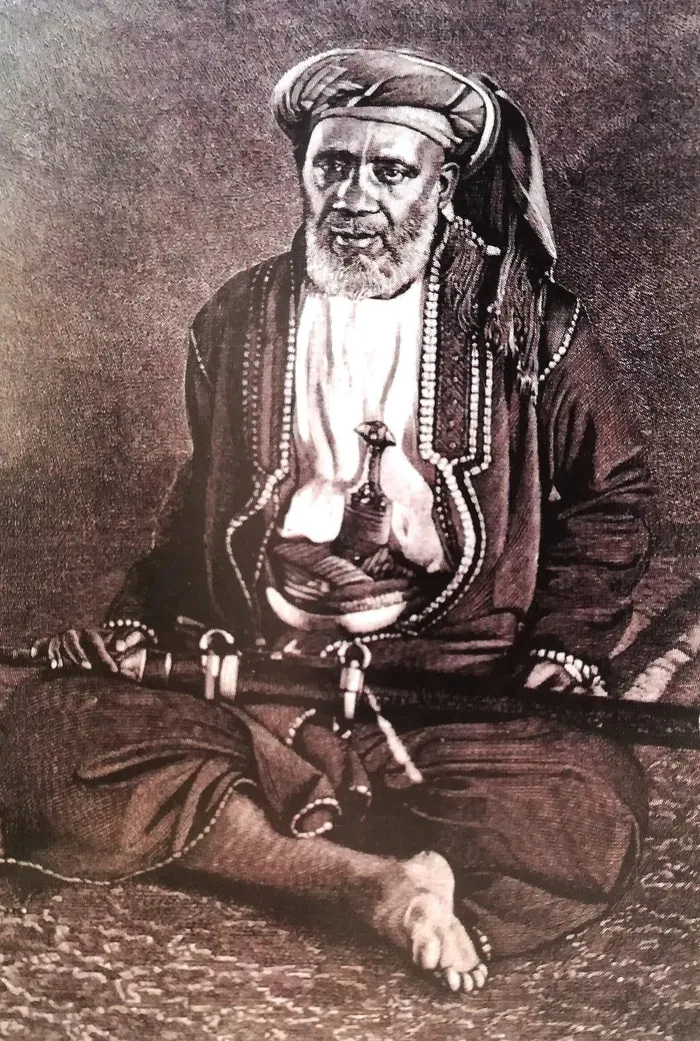

One of the most powerful and wealthy traders of this period was Zanzibar-born Tippu Tip (c 1837 - 1905), who organised annual caravans transporting slaves and ivory to the sea. The journey, over months, presented a piteous sight to those who witnessed the suffering of these captured people, the men chained together at the neck, the women carrying babies on their backs and ivory or other goods on their heads. Their feet and shoulders were a mass of open, bloody sores. Tippu Tip's aims were primarily commercial: by 1895, he owned seven plantations and 10 000 slaves.

Tippu Tip, the most important and powerful slave trader from Zanzibar.

Image: Supplied

Another state based on enslavement was the Sokoto Caliphate in Northern Nigeria and Niger. It lasted a century, from 1804 t0 1903 when Britain finally conquered it. In another fascinating snippet, Plaut mentions that at the time of the American Civil War in the 1860s, the Sokoto Caliphate had a slave population approximately the size as that in the United States. Slaves were used across the economy including in the production and dyeing of cloth.

In the Kano area alone, 50 000 dyers worked in 15 000 dye - pits. Not all slaves were treated badly, but those who “misbehaved” were savagely beaten with hippopotamus hide whips and then shackled to prevent their escape.

In 1899, Britain established the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria, instructing its first High Commissioner Sir (later Lord) Frederick Lugard to end slavery once and for all. Four years later, after military action, the Caliphate was finally defeated. Lugard’s problems though were just beginning: Britain had inherited one of the largest concentrations of slaves in the world - some two million - at a time when slavery across the British Empire had ended seven decades earlier in 1833.

Lugard’s dilemma was how to gradually free the slaves without completely collapsing the economy. As late as 1936, a census suggests that over 121 000 former slaves could still be classed as such.

Meanwhile in Ethiopia, Haile Selassie had been struggling to end slavery in his country since the 1920s. Even before his enthronement in 1930, edicts had been passed banning the slave trade, to little effect. Slavery was so ingrained in society, that even his wife had been gifted 600 slaves in 1927. When Ethiopia was threatened with military invasion by Mussolini, slaves were seen carrying funds raised by the Ethiopian aristocracy for use by the military. It was to no avail.

After the Italian invasion, Haile Selassie fled his country in 1936. Mussolini used the presence of slaves - estimated at between 300 000 and 500 000 - as a propaganda tool to legitimise his invasion. The practice was forcibly eradicated with some of the most notorious slavers executed. The Italians printed postcards showing them cutting the shackles of grateful slaves. It may have been propaganda, but it underlined the scale of the problem.

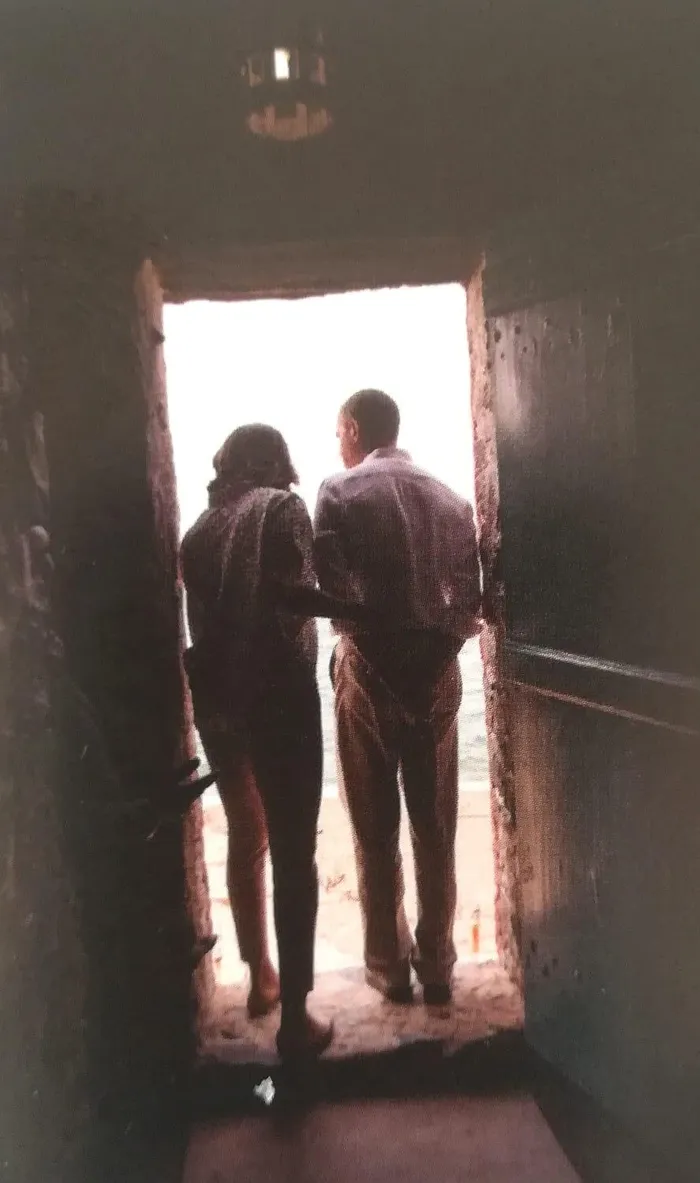

President Barack Obama and Michelle Obama at the Door of No Return, Goree Island, Senegal, June 2013.

Image: Pete Souza

European opposition to slavery developed gradually but it was largely the British abolitionists who drove the international campaign. For much of the 19th century, a major goal of British Foreign Policy was to extinguish the slave trade. Britain’s Royal Navy, operating out of Cape Town and Mauritius, began anti-slavery patrols designed to add muscle to her foreign policy. The navy patrolled a vast area of the Atlantic Ocean, increasing the number of warships off the West African coast to 35 by the 1840s.

In 1858, Britain expanded the blockade to the Indian Ocean, maintaining it until the late 1880s.

Britain had been transformed from a nation deeply involved in slavery to an active opponent of the trade, even though enforcement proved difficult and costly. At its peak, half of all naval spending was spent on suppression of the trade.

The cost was not just monetary. Over the 52 year period, 17 000 sailors lost their lives patrolling the African coast, or one sailor for every nine slaves saved.

As one First Lord of the Admiralty bitterly complained in 1876: ‘Philanthropy costs money.”

Yet for some Africans, “Britain’s naval flag, the Union Jack, became a symbol of liberation.

What to do with the liberated slaves was a constant problem as most were far from their homes.

Britain settled 80% of them in her colonies. One group of 64 children from Ethiopia was taken to the South African mission station of Lovedale in the Eastern Cape where they were well-cared for and educated.

Between 1873 and 1877, Durban received 502 freed slaves including six month old babies. The adults were given employment by Natal farmers, various businesses, the Public Works Department, the hospital and Port Captain, earning a reputation as good workers.

The emphasis on the Trans-Atlantic slave trade has masked a much larger trade in human lives which has blighted Africa for 5000 years. African slavery might have differed from American slavery, but it was still slavery. As far as the Atlantic trade is concerned, the usual suspects were rounded up a long time ago, but as Plaut so ably reveals, there were countless other suspects who slipped through the net.

Related Topics: