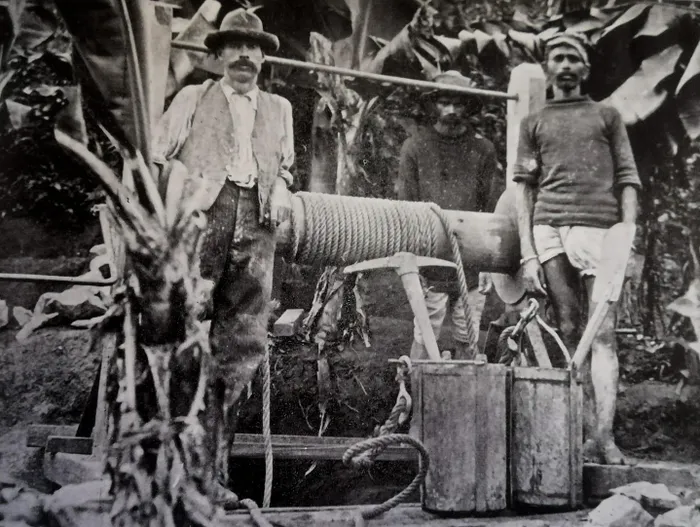

Nat Young and his assistants with his prospecting shaft at Malvern, 1907.

Image: Supplied

THE discovery of gold in 1886 on the Witwatersrand led to “a delirium of gold fever “ with countless gold mining companies being floated. In Natal, prospectors hoped to find similar riches, if not gold then diamonds. Over the next two decades, there were frequent announcements of promising new discoveries which invariably amounted to nothing.

In Zululand, there were periods of intense prospecting but most of the small rushes failed. Although there was gold, the reefs were difficult to access and there was nothing to equal the Witwatersrand reef. The Mfongosi gold rush of 1886 in the Nkandla district grew so quickly that a weekly mail service was instituted from Greytown to the Mfongosi goldfields.

With 2000 claims registered, a digger camp became a village. A year later, it was all over, ending the first major gold rush in Zululand. Prospectors followed the rumours and descended on new “discoveries”.

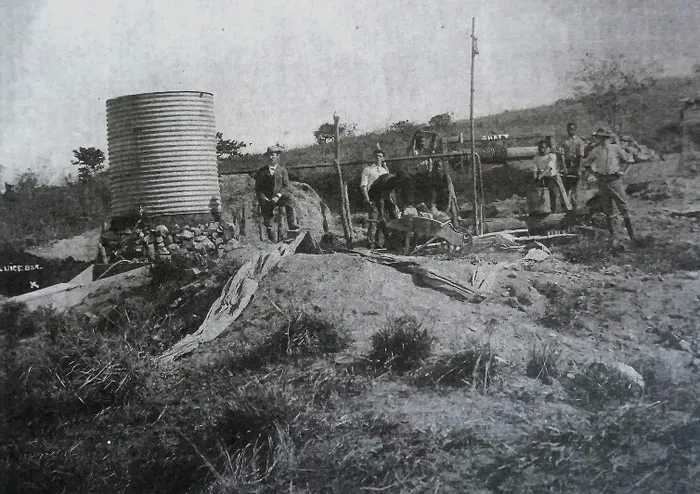

The staff of the Natal Phoenix Gold Mining Company at Inadi near Greytown, 1907.The mine did produce gold in Natal.

Image: Supplied

Companies opened and closed as rapidly as the "discoveries" fizzled. One was the Natal Phoenix Gold Mining Company which produced small amounts of gold at Inadi near Greytown but there was not enough gold to maintain profitability. There were numerous small-time operators such as Nat Young who began prospecting at Malvern in 1905.There is an extraordinary photograph of him all but lost among the banana palms in 1907, still believing that he would find a gold-bearing reef.

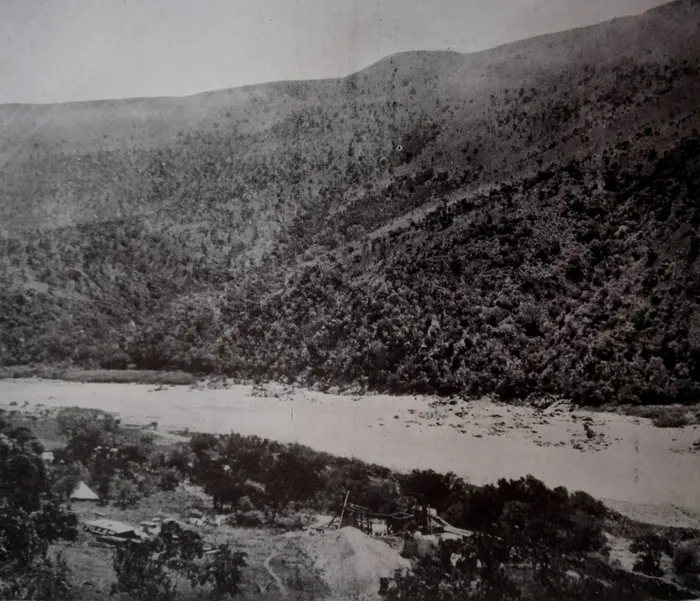

The gold mine at Chaka's Kraal in 1890.

Image: Supplied

The sugar estates were not exempted from the excitement. In 1890, a small group of hopefuls opened a mine at Chaka’s kraal. Their operation was hopeless: they should have stuck with sugar.

The profusion of diamond companies and syndicates provoked a satirical column in The Pictorial in March 1907 with the title "A new epidemic”. The dazzle of the diamond was behind the malady. Because the country had given birth to one Kimberley and one Johannesburg, a section of the public believed that Kimberleys and Johannesburgs could spring up anywhere on the sub continent. The columnist noted that owners of well-established businesses closed them down to take advantage of the “bright prospects” as it would be a mistake or a crime not to be a budding millionaire.

The area where the Natal Phoenix Gold Mining Company had its claim. It built a road to its site, later trying to recover the cost from the Natal government.

Image: Supplied

Unfortunately, there were reports of the insolvency of persons once reputed to be well to do. Durban, like the rest of South Africa, was peculiarly susceptible to this epidemic but despite warnings of caution, it continued to spread like a contagion.

Syndicates acquired options over farms in the vicinity of “proved diamond mines” and then confidently stated that there were indications of a diamondiferous pipe. Not wanting to miss out, outsiders could invest their cash in the syndicate, placing themselves in an “ advantageous position.”

The columnist drolly observed that the gentlemen who formed these syndicates were all honourable men, of course, and they were so generous they did not wish to keep all the good things exclusively to themselves. With the public appetite whetted, the promoter had his opportunity.

All but hidden among the banana palms of Malvern, is Nat Young in the foreground prospecting for gold, 1907.

Image: Supplied

Prospectors were not limited to South Africans. In 1907, an Australian visited the Williams family on their 200 acre farm in Westville. He was given permission to dig and discovered "a number of diamonds and rubies.” Fifty years later, the widowed Mrs Williams, by then an old lady of 88, recalled that find, commenting that no diamonds were found on any other farms. Her husband stopped prospecting because it caused so much ill-feeling.

"The diamonds brought only trouble and bad luck.” It certainly never brought wealth: by the 1950s, the farm had been reduced to just 10 acres and that did not last much longer. Yet Mrs Williams still insisted that a rich diamond seam still ran through the original farm. Who knows, perhaps a Westville school pupil will discover a diamond in the middle of a sports field.

Percival Langford Williams with his wife Mary and their four children, late 1890s. Westville never became the next Kimberley but Langford and Williams Roads are named after them.

Image: Supplied

Today, the gold and diamond rushes are remembered for their failure, if they are remembered at all. Let us end with the aside by “Fastidious” (an early version of the Mercury’s Idler) in March 1907: “The report that the suburbs have been visited by an earthquake is denied. The widespread disturbance of the earth's surface has been caused by the energetic digging for diamonds and the sinking of gold-mining shafts in the suburban gardens and mealie patches. Vegetation will be scarce in the suburbs next season.