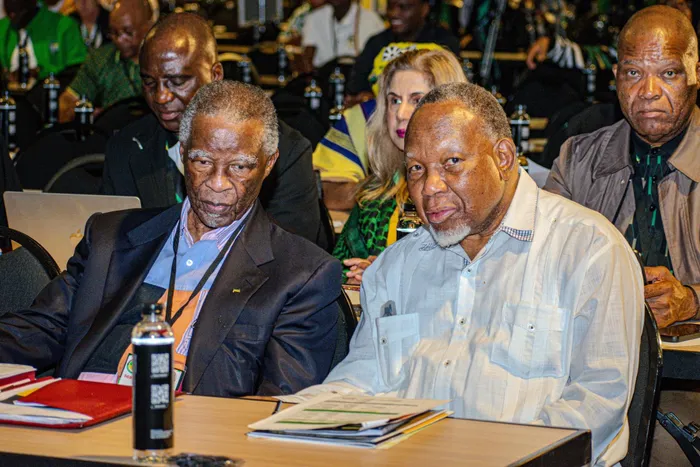

FORMER ANC president Thabo Mbeki (left) and Deputy President Kgalema Motlanthe participated in the party’s 5th National General Council (NGC) in Benoni. By giving so much prominence to organisational renewal, the NGC 2025 conceded that not sufficient progress has been made, says the writer.

Image: ANC/X

Prof Dirk Kotze

The ANC’s National General Council (NGC) is an organisational oddity, and few members of the public actually know what to expect of it. It is not a conference, and it does not elect party leaders. It is also not a policy-making body.

The ANC established it in 2000, and its mandate is to be a mid-term event where progress made with the implementation of the preceding National Conference resolutions is evaluated. It is normally held quite close to the next local government elections.

This year’s NGC is different in the sense that it is the first meeting of its kind in 10 years. The one meant for 2020 did not materialise because of the COVID-19 pandemic. NGCs are not to be action-packed events, but are characterised by long commission sessions.

An exception was, however, the one in 2005. President Mbeki dismissed Jacob Zuma as national deputy president two weeks before the NGC at Pretoria University. Mbeki also determined that, though Zuma continued as the ANC Deputy President, he could not attend any ANC activities.

The NGC, however, rebelled against it and reinstated Zuma’s ANC status. In the same vein, the NGC 2025 was seen as an opportunity for the Ramaphosa critics to orchestrate moves against him, but nothing materialised despite the ANC’s dramatic losses in the 2024 national/provincial elections.

How can that be explained? Since his re-election as ANC President in 2022, he has systematically strengthened his position in the ANC’s National Working Committee and National Executive Committee (NEC) by following an indirect approach.

The formation of the uMkhonto weSizwe Party (MKP) under the leadership of President Zuma in 2023 also created a new political home for the Radical Economic Transformation (RET) faction in the ANC. The result has been a significant reduction in the ANC’s factionalism and has consolidated Ramaphosa’s power.

This does not mean that a policy or ideological consensus has descended onto the ANC. Like in the past, because it is still a broad “church” of political convictions, it will always make policy coherence in the party very difficult.

The NGC 2025 did not succeed in improving the situation. In the absence of any radical deviations, it actually reinforced and legitimized the policy approaches of Ramaphosa since the 2022 National Conference. That includes his macro-economic repositioning to incorporate prominent private sector partnerships with the state sector in most of the SOE functions, particularly in energy, transport, and infrastructure.

Describing his foreign policy as applying the principle of non-alignment in line with the Freedom Charter’s clause 10, and on the back of his G20 presidency, it made any serious criticism of his policy positions very difficult. Ramaphosa appears to approach his role as a national president more like a diplomat than as a politician. The result is the absence of spectacular, fast-moving outcomes but also the absence of serious dissent in public within his close circle.

As part of this approach, Ramaphosa has systematically underplayed the Tripartite Alliance with COSATU and the SACP. The NGC 2025 did not provide them an opportunity to push back on the Ramaphosa approach.

While COSATU in its current, weaker form – after its split with SAFTU in 2017 - does not appear to have the appetite to confront Ramaphosa directly, the SACP is in a different position. They have decided to deviate from their electoral cooperation with the ANC in the 2026 local government election.

But the NGC did not reveal in public new tensions between the two organisations. The Party’s unilateral approach actually enabled Ramaphosa to adopt a more centrist approach before the 2026 election.

The NGC 2025 combined two elements in its conference theme: the party’s organisational renewal and its embracing of the Freedom Charter. The objective of the ANC’s organisation renewal was fully sanctioned by the 2022 National Conference. But the Renewal Commission, which had to take the lead in it, was only established three years later.

Though the renewal theme featured at most subsequent NEC meetings, the absence of the Commission meant that only uncoordinated, though significant, steps were taken. For example, its membership system has been modernised. The Election Committee had been established to manage the party’s participation in elections. All ANC members must now attend a foundational course to improve their knowledge of the ANC.

But these renewal steps compete with the public impressions of the Madlanga Commission and the parliamentary ad hoc committee that exposed ANC members and ministers. Evidence of unethical and criminal acts is seen by the public. By giving so much prominence to organisational renewal, the NGC 2025 conceded that not sufficient progress has been made. Public opinion polls make it abundantly clear.

The 70th anniversary of the Freedom Charter was the reason for the second part of the conference’s theme. It served the purpose of legitimizing the proposed renewal as a return to the ANC’s philosophical roots, as stated in the Charter. History always provides a safe retreat for the ANC. By justifying its actions in terms of the Charter, it diverts attention away from criticism that it did not act on the conference mandates that it received over a period of 30 years.

The expectation that the ANC has to conclude its transformation from a liberation movement to a modern parliamentary political party remains unmet. The NGC 2025 also did not change this perception. Many would say that it was a last–but–missed opportunity for the ANC.

At the NGC, the ANC’s analytical framework developed in exile remained the constructs of geostrategic balance of forces, a national democratic revolution, and the SACP’s national question. Much of that goes back to the first Strategy and Tactics document of the 1969 Morogoro conference. That appeases the Tripartite Alliance and the ANC’s former exile community, but is beyond most young voters.

In a very honest way, the NGC conceded its current predicament in terms of declining popular support and acknowledged that the 2026 local government elections pose a serious threat to it. At the same time, the event endorses President Ramaphosa despite speculations of his resignation after the G20, as well as speculations of succession.

Ramaphosa exited the NGC stronger than when he entered it, though the political risks faced by the ANC remained largely unchanged. Its renewal is not about organizational renewal but about renewal of how it governs and how its members conduct themselves as public representatives.

* Prof Dirk Kotze, Department of Political Sciences, Unisa.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.