The function and relevance of lobolo in contemporary society has brought much discussion across different landscapes. The Constitutional Court's recent ruling on customary marriages protects equality but creates unexpected consequences. Learn how traditional ilobolo celebrations can now legally constitute marriage, and why couples need legal advice before celebrating traditional steps toward marriage.

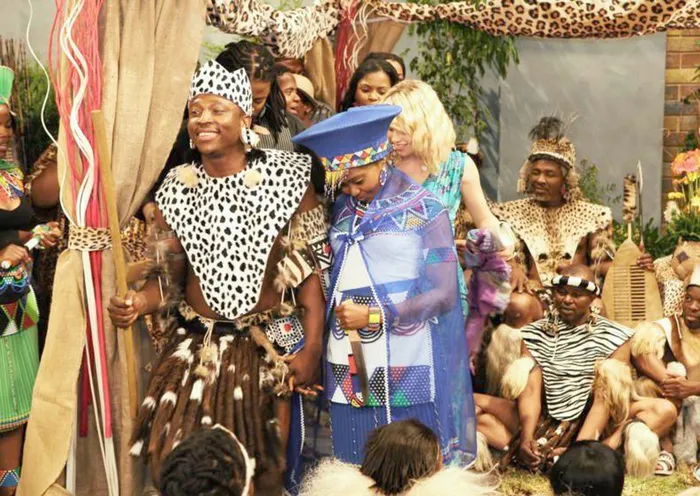

Image: Supplied

On January 21, 2026, the Constitutional Court in Mbungela v. The Minister of Home Affairs and Others delivered a judgment that is rightly celebrated as a victory for equality. By ruling that antenuptial contracts signed after ilobolo (the bride price) and the conclusion of a customary marriage are invalid, the Court affirmed that customary marriages stand on equal footing with civil marriages. It closed the door on opportunistic attempts to strip spouses, often women, of their rights to the joint estate.

Historically, the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act of 1998 set out clear requirements: the marriage must be negotiated, entered into, or celebrated in accordance with customary law; both parties must be over 18; both must consent; and the marriage must be negotiated and celebrated between families, usually involving ilobolo. In the early years, courts interpreted these requirements narrowly, often demanding strict proof of ilobolo negotiations, the presence of elders, and a formal “final” celebration. Many unions were excluded from recognition, leaving women and children vulnerable.

Over time, however, courts widened the catchment. In cases such as MM v. MN (2013) and Mbungela v Mkabi (2019), judges recognised that customary marriages are living institutions that evolve with society. They accepted that partial or adapted celebrations, a family lunch, an exchange of gifts, or symbolic ceremonies could constitute sufficient evidence of a valid marriage. This pragmatic approach aligned customary law with constitutional values of dignity and equality, but it also blurred the line between betrothal and marriage.

That evolution now collides with cultural practice. For black South African couples, marriage is often seen as a process of staggered celebrations: ilobolo negotiations, often a celebratory lunch, a gifting ceremony, and later a wedding reception or umgcagco. Yet the law does not wait for the “final” step. The moment ilobolo is celebrated, the law may deem the marriage valid. What a couple might view as a simple family gathering, the law can interpret as a marriage celebration, binding them in community of property.

Social media has amplified this risk. Wedding-like gifting ceremonies and ilobolo celebrations are increasingly staged with grandeur and shared widely online. These events, while culturally joyous, can be read by the law as evidence of a completed marriage. Couples who believe they are still betrothed may in fact already be legally married, with all the consequences that flow from that.

The Constitutional Court’s ruling is a triumph for dignity and protection, but it also demands vigilance. Couples must understand that in the eyes of the law, intention and celebration matter. What feels like a step along the way may already be the destination. The risk is that without careful planning, families may find themselves bound by a joint estate before they ever thought the marriage had formally begun.

This is the paradox of progress. Equality has been strengthened, but the cultural fluidity of staggered celebrations now collides with the rigidity of legal recognition. The challenge for black South Africans is to navigate this terrain with eyes wide open, ensuring that tradition is honoured while the law’s consequences are understood.

As a takeaway note, if you intend to marry out of community of property, it is essential to seek legal advice before any ilobolo celebrations. An antenuptial contract must be signed and registered prior to the marriage being celebrated. Once ilobolo is celebrated, the law may already recognise the marriage as valid and automatically in community of property. This means a joint estate is established, and each spouse becomes jointly responsible for the assets and liabilities of the other. In practice, either spouse can be sued for the debts of the other, and property acquired by either becomes part of the shared estate. Any antenuptial contract signed afterwards will be invalid.

(Nomvalo is an admitted attorney of the High Court of South Africa and an advocate for women and children's rights. Her views don't necessarily reflect those of the Sunday Tribune or IOL)

Nqolokazi Nomvalo is an admitted attorney of the High Court of South Africa who advocates for women and children's rights

Image: Supplied