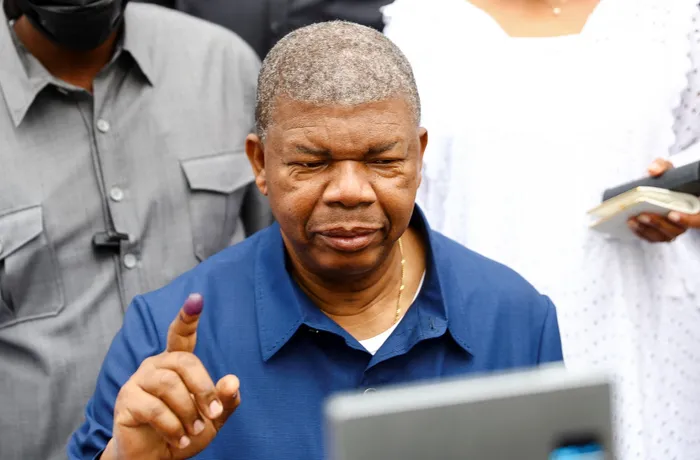

Angola's President and leader of the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) ruling party.

Image: Siphiwe Sibeko / Reuters

YOU can feel it in the language of the nomination letter and in the quiet confidence of Angolan diplomacy today: João Lourenço’s name on the Nobel Peace Prize shortlist is not a vanity flourish but the natural culmination of years spent turning reconciliation into a governing doctrine and dialogue into a foreign-policy tool.

For a country that lived through nearly three decades of civil war, the symbolism is profound. Angola is no longer only a story about how a nation survives conflict; under Lourenço, it is a story about how a nation helps others avoid it. That is why this moment resonates across English-speaking Africa. It says something larger than a single man’s candidacy. It says the continent’s peacemaking is maturing — and the world has begun to notice.

Lourenço’s case for the prize rests on work, not theatrics. As head of state, and in concert with the African Union (AU), he has insisted that African crises deserve African solutions anchored in negotiation. He pressed for stability in the Great Lakes region at a time when mistrust and misinformation threatened to harden into a permanent fracture. He convened leaders, absorbed pressure from multiple sides, and made Angola a venue where adversaries could speak without losing face.

Mediating efforts touching the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Rwanda, and the Central African Republic were not clean or easy, yet they carried a consistent message: cease the escalation, open the channels, build the habits of contact that make peace sustainable rather than performative. Even his critics concede that when tensions rose, Lourenço kept showing up with the same steady prescription — talk, verify, de-escalate, repeat.

That regional posture was matched by an unapologetically principled voice on global questions. When he spoke about reparations for historical slavery during Africa Day celebrations, it was not as a sloganist but as a statesman connecting justice to stability. The argument was simple: enduring peace requires that the international system treat African grievances as legitimate claims, not as inconvenient noise.

Similarly, he urged a more balanced partnership with Europe, one that moved beyond paternalism toward reciprocal value. His earlier interventions on migration, calling out the human cost and the shared responsibility of origin and destination states, fit the same pattern. If the objective is fewer tragedies and less trafficking, the answer is development, dignity, and orderly channels — not denial.

At home, Lourenço’s credibility rests on the hard politics of reform. He carried forward national reconciliation after the war not as a periodic ceremony but as a daily administrative choice. He tolerated the discomfort that comes with pursuing accountability, including against figures close to Angola’s old power structures. He pushed for cleaner governance, sought to draw investment toward infrastructure and industry, and argued that a country that treats its people fairly projects stability outward.

Peace is not a press release. It is jobs, schools, roads, courts that function, and institutions people trust enough to use instead of picking up a gun. In that sense, Lourenço’s domestic agenda has always been the ground floor of his regional diplomacy.

The nomination letter submitted on his behalf captures this arc. It frames his candidacy as recognition not only of an individual but of Angola’s transformation—of a society that chose dialogue after devastation and then exported that instinct to its neighbourhood. It notes the international respect he has earned as a mediator and the way peers publicly credit him for lowering temperatures, particularly in the eastern DRC.

It points to the consistency of his message inside the African Union: cooperation over grandstanding, pragmatic steps over empty bravado. If the Nobel Peace Prize is meant to honour those who make the world safer through patient, principled engagement, the contours of Lourenço’s record fit.

The comparison with US President Donald Trump is unavoidable because both names are now in the same conversation and because the contrast is so stark. Trump wants the prize; Lourenço appears to have earned consideration for it. Trump is adept at headline diplomacy, announcing peace frameworks with much fanfare, then moving on.

Lourenço, by temperament and training, has been the opposite: fewer superlatives, more shuttle meetings; fewer cameras, more communiqués that actually change the security dynamics on the ground.

Trump’s critics warn that his bid is wrapped in spectacle and marred by choices that run against the grain of peacemaking. They point to his elimination of America’s main development-aid apparatus, a move that humanitarian leaders said would worsen famine, disease, and displacement in precisely the fragile contexts where peace is hardest to build.

They recall his unblinking political support for the Gaza war even as civilian suffering mounted, and his refusal to use Washington’s leverage to pursue a ceasefire. They note the repeated public threats to deploy US troops against allies or neighbours, and the readiness to authorise lethal strikes far from traditional battlefields without a clear legal basis or diplomatic horizon.

And they argue that several of the “historic” deals he claimed either never existed in the form described or were designed more as public relations than as durable settlements, leaving underlying conflicts to smoulder once the cameras turned away.

This is not a debate about whether Trump did anything at all that touched the word peace. It is a debate about what kind of peace the Norwegian Nobel Committee is supposed to reward. There is a peace of announcements, which flares bright and burns out. And there is a peace of institutions and habits, the kind that creeps into a region because leaders decide to make calls at tense hours, to reopen roads, to exchange prisoners, to tighten borders against militias without strangling commerce, to stop rewarding maximalists and start empowering those willing to compromise.

Lourenço’s approach belongs to the second category. It is the less glamorous peace, the more honest one, and the only kind that tends to last.

For English-speaking Africa, backing Lourenço’s candidacy is not parochial cheerleading. It is a statement about standards. The continent knows what real peacemaking looks like because it pays the price when the real thing is absent. It knows that aid cutoffs don’t reduce conflict, that performative “deals” can be worse than no deal at all, and that threatening force to win headlines only pushes communities deeper into fear.

It also knows what it means when a country that once bled learns to help others stop bleeding. Angola’s evolution from battlefield to mediator is a continental asset. Rewarding the leadership that shepherded that change would not only honour a record; it would encourage a model.

The Nobel Committee, of course, will decide on its own criteria. But history remembers whether the prize elevated substance or indulged spectacle. If the choice is between a leader who treats peace as a campaign prop and a leader who treats it as statecraft, the argument should not be difficult.

Lourenço has shown that patient diplomacy, anchored in reconciliation at home and responsibility abroad, can move the hardest problems a few vital inches toward resolution. That is what the prize was created to recognise. And that is why, in this moment, Angola’s president is not just a compelling nominee; he is the standard against which the rest should be measured.

* Dr Eric Hamm is a professor of political science and a strategic researcher. The views expressed here are his own.

** The views expressed here do not reflect those of the Sunday Independent, Independent Media, or IOL.

Related Topics: