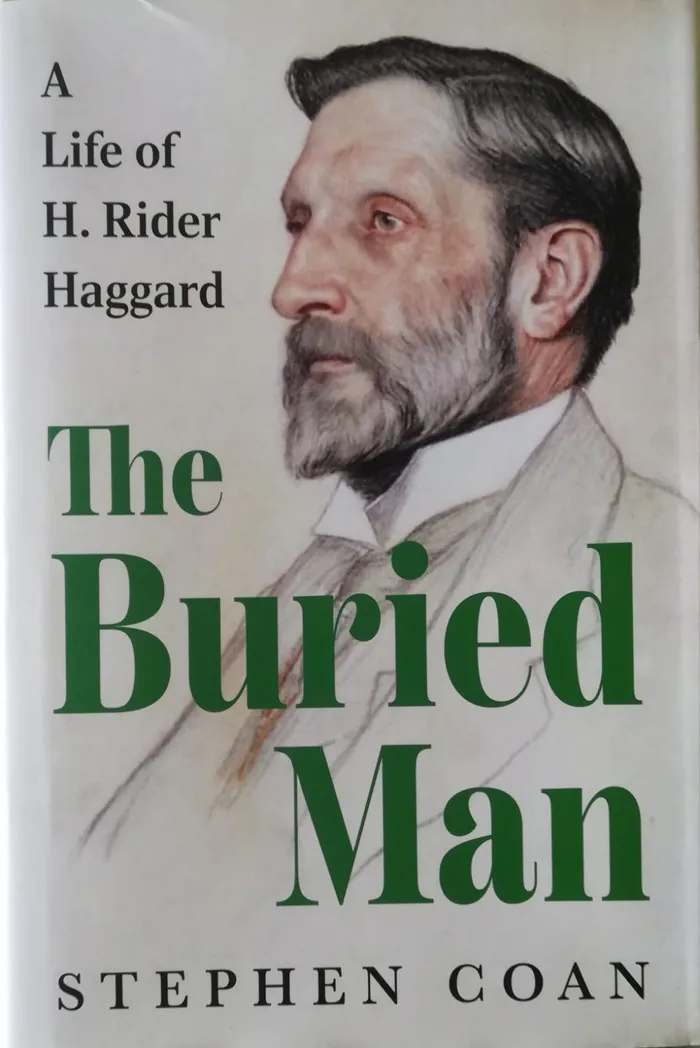

The cover of Stephen Coan's substantial biography on Rider Haggard.

Image: Supplied

"Just before you come to Durban there is a peculiar richness about the landscape. There are sheer kloofs cut into hills by the rushing rains of centuries, down which rivers sparkle; there are the deep greens of the bush as God planted it, while now and again a white house, smiling out at the placid sea, puts a finish and gives an air of homeliness to the scene.”

These lines from King Solomon’s Mines are narrated by the hunter-trader Allan Quatermain, who lived on the Berea in a small brick house with a galvanized roof and fruit trees in the garden.

The author was the 29-year-old H. Rider Haggard. Published in 1885, his novel was an immediate success and has never been out of print. It quickly engages, pulling the reader into a compelling adventure story akin to Indiana Jones, a character directly descended from Allan Quatermain.

The vivid and lifelike colours of Haggard’s Africa - based novels are derived from the period during which he lived in Natal and the Transvaal between 1875 and 1881. Born in Norfolk in 1856, Haggard was at something of a loose end after completing his schooling. Although his academic career was unremarkable, he did win a prize for “the best descriptive essay.”

Rider Haggard at about the time he arrived in Natal in 1875.

Image: Killie Campbell Library

In 1875, his father heard that Sir Henry Bulwer, whose family were old friends, had been appointed to the Lieutenant - Governorship of Natal. After a great deal of persistence from Haggard’s mother, Bulwer agreed that young Rider - just 19 - could join his staff as an unpaid secretary. As a consequence, he had to rely on his father for regular financial support while in Bulwer’s employ. He once wrote home apologising for his dependence, but at least “I will cost less than if I had been at home.”

In a new biography, The Buried Man: A life of H. Rider Haggard (Hurst, 2025), Stephen Coan examines these South African years in greater detail than previous biographers. Many years later, Haggard returned to South Africa on official business. By then he was no longer the callow youth of 1875, but a famous best -selling author who had been knighted in 1912. It is often presumed that his knighthood was for his literary achievement when in fact it was for his public service and agricultural expertise.

It was during these early years of working for Bulwer and then Sir Theophilus Shepstone that the callow youth absorbed all that fascinated him about Africa which he then wove with such skill into his most enduring novels.

Government House in Pietermaritzburg in 1901 after a new wing had been added. Haggard spent a year living in the Governor's official residence which he described as a "very pretty building".

Image: Supplied

Durban in the 1870s was still a small town, but the Royal Hotel had established something of a reputation and was where the new Governor and his unpaid secretary spent their first nights before departing for Government House in Pietermaritzburg.

After meeting Haggard, Major General Sir Garnet Wolseley wrote in his diary that he was a “leggy-looking youth not long out of school who seems the picture of weakness and dullness.”

As Bulwer was a bachelor, Haggard was expected to supervise all the entertainment at Government House. He enjoyed life in the Natal capital, declaring the climate magnificent and the scenery fine. He also acquired a personal helper, Masuku, who is a major character in Haggard’s novel, The Witch’s Head.

When Bulwer went up-country to familiarise himself with Natal, he took Haggard with him. The trip was led by Theophilus Shepstone whom Haggard came to admire. On this tour, his eyes were opened to the dramatic qualities of the African scenery, culture and customs of the Zulus. After a year with Bulwer, Haggard asked for a transfer to Shepstone’s staff. It was a while before Bulwer agreed.

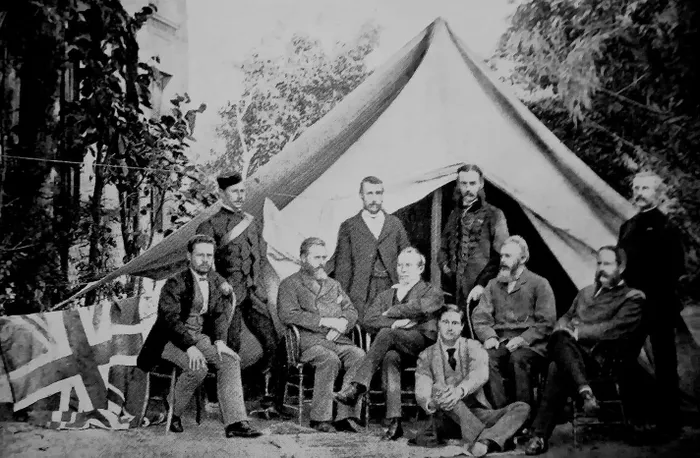

Theophilus Shepstone (seated centre) with his staff on April 12, 1877, the day of the annexation of the Transvaal. Haggard is seated on the ground.

Image: Supplied

The transfer came at a pivotal point in the Transvaal’s history, with Shepstone playing a key role. On April 12,1877, it was declared a British territory. In Pretoria’s church Square, the Proclamation was partly read by Haggard himself after Melmoth Osborn stumbled over the text.

The following month, on Queen Victoria’s birthday, the Union Jack was raised. Together with Col. Brooke, Haggard did the honours of calling it “one of the proudest moments of my life.”

Financially, it was also significant as he was appointed to the first of two salaried posts he held while in the Transvaal. The second post, in 1878, as Master and Registrar of the single - judge High Court was extraordinary. Haggard was not yet 22 and had never studied law, but appears to have learnt on the job. After his return to England, he chose to practise law and was called to the Bar in 1885.

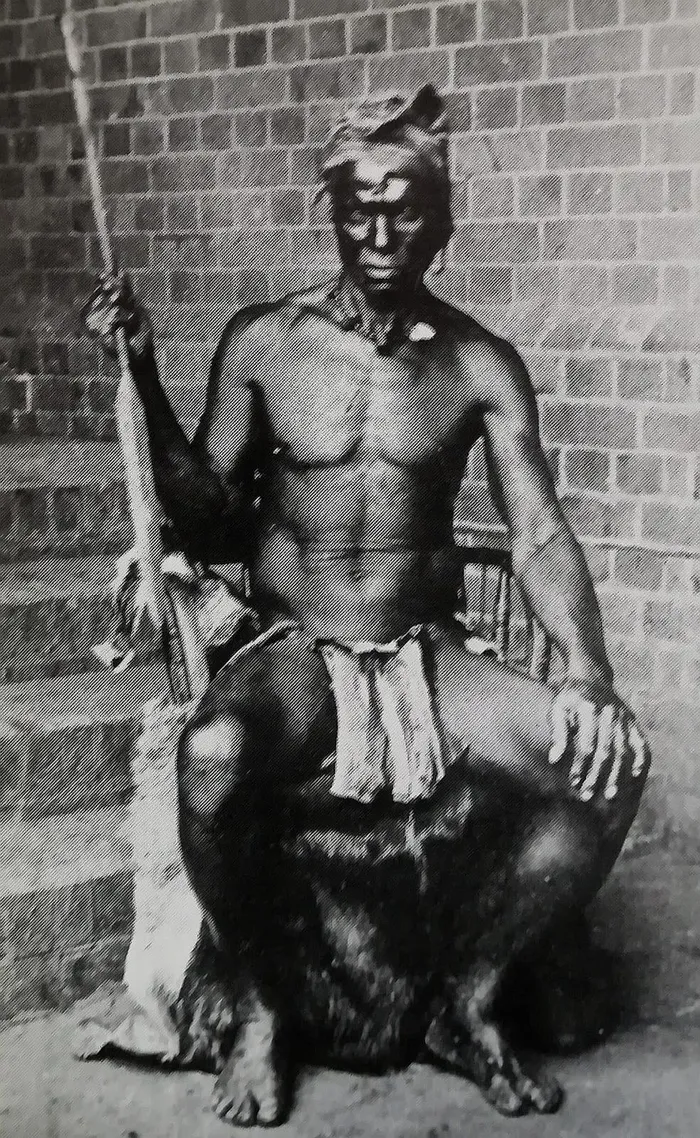

Two men impressed Haggard. One was Paul Kruger, the other was Shepstone’s head attendant, Mhlopekazi, a Swazi of reputed royal birth who appeared as a major character in three of his novels, Allan Quartermain (1887), Nada the Lily (1872) and She and Allan (1921).

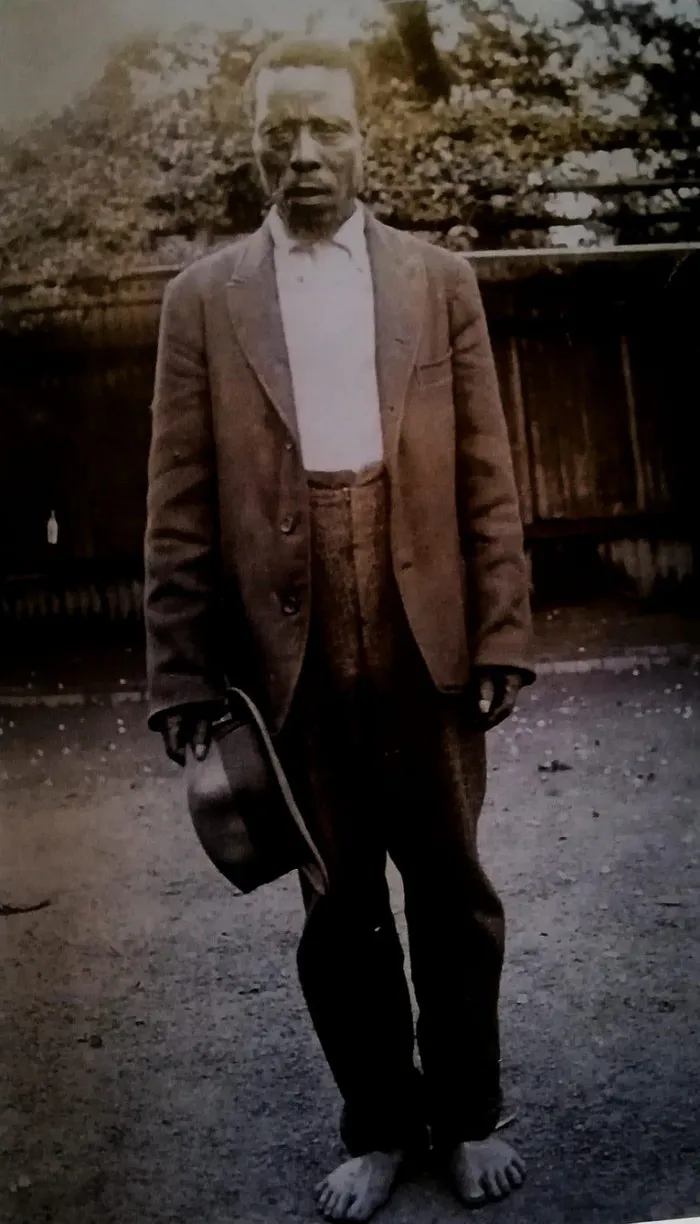

Mhlopekazi in the 1870s on the staff of Shepstone. He became famous as Umslopogaas in three of Haggard's novels.

Image: Supplied

The latter two appeared after Mhlopekazi’s death, but before he died in 1890, he was aware of his fame as the character Umslopogaas.

Haggard resigned in May 1879 and together with his friend and colleague, Arthur Cochrane, bought a farm, Hilldrop, outside Newcastle. He then returned home. There he met the 20 -year-old Louisa Margitson, proposing to her three days later. He married for love but had the good fortune to fall in love with an heiress with money and land. They wed in August 1880 and together sailed for Natal to begin married life at Hilldrop.

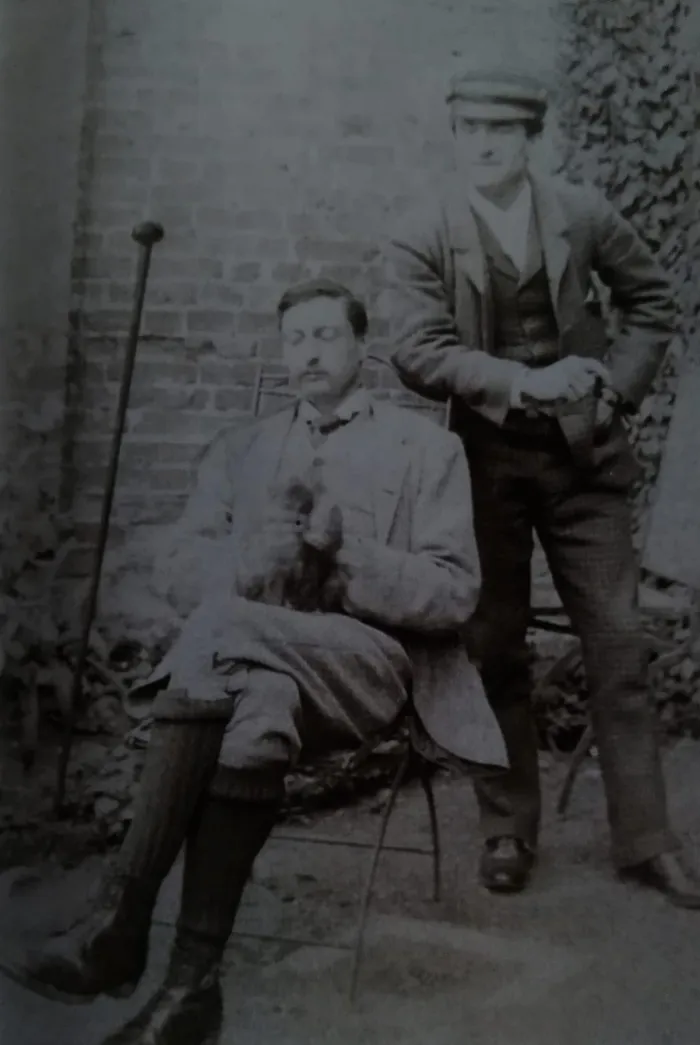

Haggard (seated) and Arthur Cochrane shortly after their return from Natal in 1881. Masuku's knobkerrie is planted in the flowerbed.

Image: Supplied

Their arrival coincided with another pivotal point in the Transvaal’s history. The British annexation in 1877 had not gone down well, but Britain refused to reverse it until the Battle of Majuba when the might of the British Empire was humbled by a small Boer republic with no standing army.

Lady Louisa Haggard at Ditchingham, which she inherited.

Image: Supplied

Britain entered into peace negotiations with the Boers, and in need of a venue asked if Hilldrop could be leased from April 1881. Haggard agreed, except for their bedroom, which the pregnant Louisa continued to use. It was just as well: while the negotiations were proceeding, Louisa gave birth to a son, Jock, on May 23.

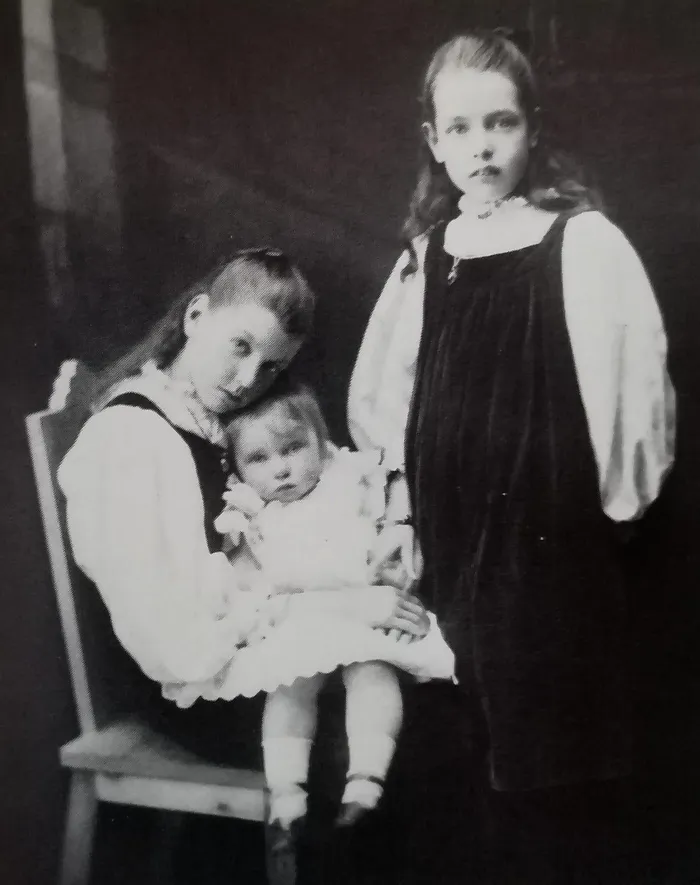

Haggard's three daughters, Angela with baby Lilias, and Dorothy in 1894. Their brother, Jock, died a few months before his 10th birthday in 1891.

Image: Supplied

In July, Haggard received a letter from his father urging him to return home. After auctioning their furniture, the young family left Hilldrop with deep sadness as “we drove down the dusty track and the familiar house grew dim and vanished from our sight.”

Masuku in 1914 when Haggard saw him for the last time. He assisted Masuku financially.

Image: Supplied

There was an emotional farewell with Masuku who gave Haggard his redwood knobkerrie stick which he had carried ever since he was a man and was probably what he valued more than anything he possessed.”

Thirty three years later, in 1914, Haggard together with Louisa and their youngest daughter Lilias, returned to South Africa. There was a moving reunion with Masuku, “now an old man” who could not believe that Haggard still had the knobkerrie stick. They parted one final time at the Maritzburg station, never to meet again. The family also visited Hilldrop, that place of “so many memories” where they once again picked fruit from the old naartjie trees.

The Hilldrop farmhouse as depicted in Haggard's Memorial Window at St Mary's church, Ditchingham in Norfolk.

Image: Supplied

After Haggard’s death in 1925, Lilias dedicated a memorial window at the family church at Ditchingham. Included in the window is a depiction of Hilldrop.

Although many of his novels are set in Africa, they have faded with time as have his works of non- fiction. During his lifetime, his novels drew praise from all strata of society. The 13 -year-old Winston Churchill wrote to Haggard telling him he liked Allan Quatermain better than King Solomon’s Mines and hoped he would write a great many more books.

Queen Victoria’s daughter who was married to the German Emperor wrote that her husband Frederick lll who was dying of throat cancer, found pleasure reading his books. Haggard later dedicated one of his novels to the widowed Empress. On a visit to the United States, a hobo on hearing Haggard’s name, exclaimed that he had read all his books, some several times. There were also the critics. Tolstoy mocked She, pronouncing Haggard’s novels “the lowest type of literature.” He was astonished how many of the English went wild over them.

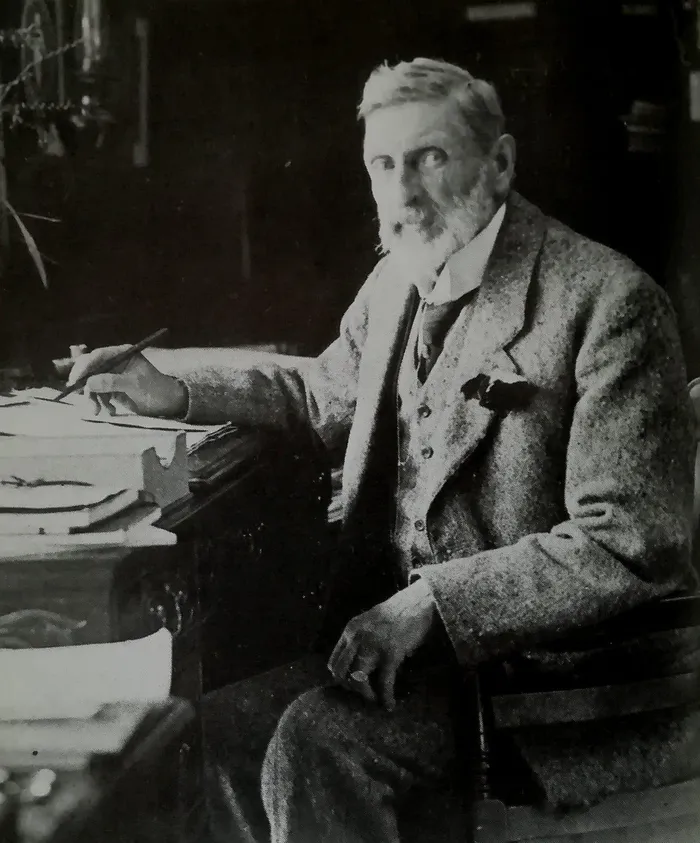

Haggard at his desk at Ditchingham in about 1920.

Image: Supplied

Today, even his most popular novels are less read, although scholars continue to show an interest. Stephen Coan is an expert on Haggard’s literary output and career. His prodigious research over 30 years with the support of Haggard’s family has uncovered lesser known aspects of the novelist’s life, including his meeting in 1914 with John Dube, the President of the ANC. The author Graham Greene referred to the private Haggard as the “buried man,” whose life only emerges in his novels.

Haggard himself admitted that Allan Quatermain, who appears in 14 books, was his alter ego “thinking my thoughts and looking at life through my eye.”

In his mammoth new biography in this the centenary year of Haggard’s death in 1925, Coan has meticulously sharpened the image of the author and the era which both defined and embraced him.

The Buried Man: A life of H. Rider Haggard is available at all good book stores.