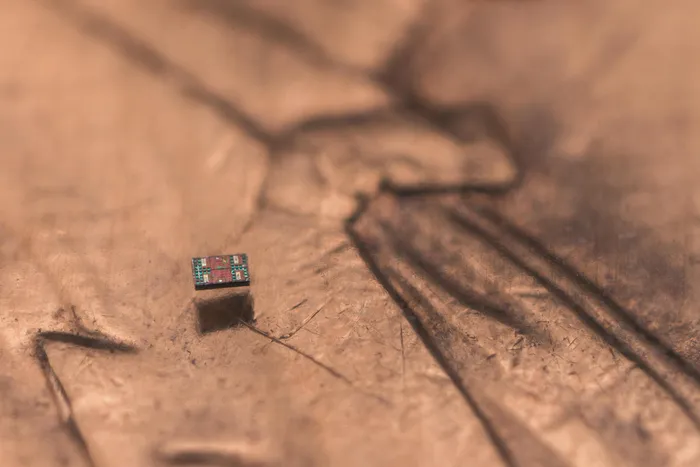

A microrobot on a U.S. penny, showing scale.

Image: Michael Simari/University of Michigan

SOLVING a technical challenge that has stymied science for 40 years, researchers have built a robot with an onboard computer, sensors and a motor, the whole assembly less than 1 millimeter in size - smaller than a grain of salt.

The feat, accomplished by a partnership of researchers at University of Pennsylvania and University of Michigan, advances medicine toward a future that might see tiny robots sent into the human body to rewire damaged nerves, deliver medicines to precise areas, and determine the health of a patient’s cells without surgery.

“It’s the first tiny robot to be able to sense, think and act,” said Marc Miskin, assistant professor of electrical and systems engineering at University of Pennsylvania, and an author of a paper describing the work published this week in the journal Science Robotics.

The device, billed as the world’s smallest robot able to make decisions for itself, represents a major step toward a goal once rooted in science fiction. In the 1960s, the story and movie “Fantastic Voyage” imagined a medical team placed aboard a submarine and shrunk to the size of a microbe. The microscopic medical crew was then injected into the body of a dying man in order to destroy an inoperable blood clot.

“In the future, let’s say 100 years, anything a surgeon does today, we’d love to do with a robot,” said David Gracias, a professor in the department of chemical and biomolecular engineering at Johns Hopkins University who was not involved in the study. “We are not there yet.”

In 1989, two decades after “Fantastic Voyage,” Rodney A. Brooks and Anita M. Flynn, scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, wrote a paper called, “Fast, Cheap and Out of Control: A Robot Invasion of the Solar System,” that described a robot they’d built measuring just 1¼ cubic inches, dubbed Squirt.

Sawyer Fuller, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Washington, said that when “Fast, Cheap and Out of Control,” was published, “people thought microrobotics was coming any minute now. … Turns out it has taken a little longer than expected to put all these things together.”

Fuller, who was not involved in building the new microrobot, called it “the vanguard of a new class of device.”

Miskin said the microrobot built by the Michigan and Pennsylvania teams is about 1/100th the size of MIT’s Squirt but isn’t ready for biomedical use.

“It would not surprise me if in 10 years, we would have real uses for this type of robot,” said David Blaauw, a co-author of the paper in Science Robotics and professor of electrical engineering and computer science at University of Michigan.

For decades scientists have dreamed of building a microrobot less than 1 millimeter in size, a barrier that corresponds to the smallest units of our biology, Miskin said. “Every living thing is basically a giant composite of 100-micron robots, and if you think about that it’s quite profound that nature has singled out this one size as being how it wanted to organize life.”

For comparison, a human hair has a diameter of about 70 microns, while human cells are about 20 to 40 microns across.

Although scientists and engineers have been miniaturizing circuits for the last half-century, the challenge has been to shrink all of the parts needed for a computer-guided microrobot, then assemble them without damaging the parts or causing them to interfere with one another. The robot needs an energy source of sufficient power to operate the computer and move the robot.

Five years ago, Miskin, whose specialty has been building microrobots, met Blaauw when the two gave back-to-back talks. Blaauw’s lab then held ― and still holds ― the distinction of having built the world’s smallest computer.

“Even in the presentations we were like, ‘Oh, we need to talk to each other,’” Blaauw recalled.

The device they built uses tiny solar cells that convert light into energy. Some of that energy powers the computer, and some propels the robot as it swims through liquid. The computer runs at about one-thousandth the speed of today’s laptops and has far less memory.

In the lab, the scientists shone an LED light down into the lab dish that contained the robot in a solution. The robot is made of the same kinds of materials found in a microchip: silicon, platinum and titanium.

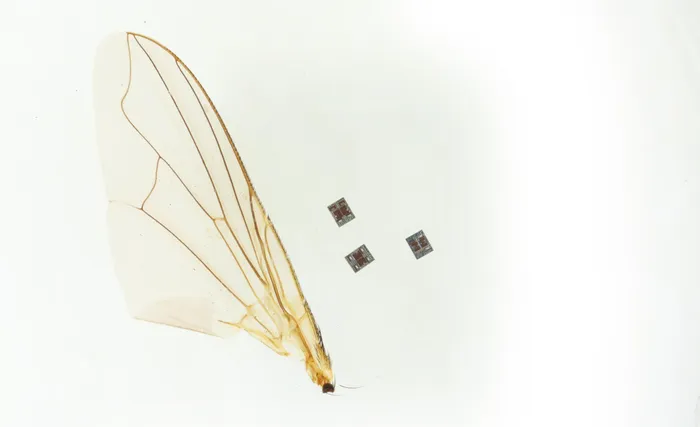

Three microrobots beside an insect wing, for scale.

Image: Maya Lassiter/University of Pennsylvania

To protect it from the effects of fluids, the microrobot is encased in a thick layer of what is essentially glass, Miskin said. There are a few holes in the glass that are filled in with the metal platinum, forming the electrodes that provide electrical access.

At Johns Hopkins, Gracias stressed that scientists need to ensure that the materials they use for microrobots can be safely used inside a human body.

Sensors on the robot allow it to respond to different temperatures in liquid. To move, the device uses energy from the solar panels to charge two metal electrodes on either side of it. The electrodes attract oppositely charged particles in the water, generating a flow that pulls the robot along.

As it swims, the robot communicates with the person operating it.

“We can send messages down to it telling it what we want it to do,” using a laptop, Miskin said, “and it can send messages back up to us to tell us what it saw and what it was doing.”

The robot communicates using movements inspired by the waggle dance honeybees use to communicate.

During the summer, the scientists invited a group of high school students to come in and test the new microrobots. The students were able to track the movements of the robots using a special low-cost microscope.

“They loved it,” said Miskin. “It was definitely a little bit challenging at first, just getting oriented to working with something that small. But that’s part of the appeal. Once they got the hang of it, they were all in.” Miskin said the version of the robot the students used cost only about $10.

Researchers are working now to develop the microrobot so that it can work in saltwater, on land and in other environments.

The long-term vision, Blaauw said, is to design tiny computers that can not only talk back and forth to their operators.

“So the next holy grail really is for them to communicate with each other,” he said.

Related Topics: